Valentin Carron proved to be a precocious artist and began studying art at the age of fifteen, first at the École cantonale d’art du Valais and then, concomitantly, at the École cantonale d’art de Lausanne. He eventually graduated with a degree from both institutions, in 1999 and 2000 respectively.

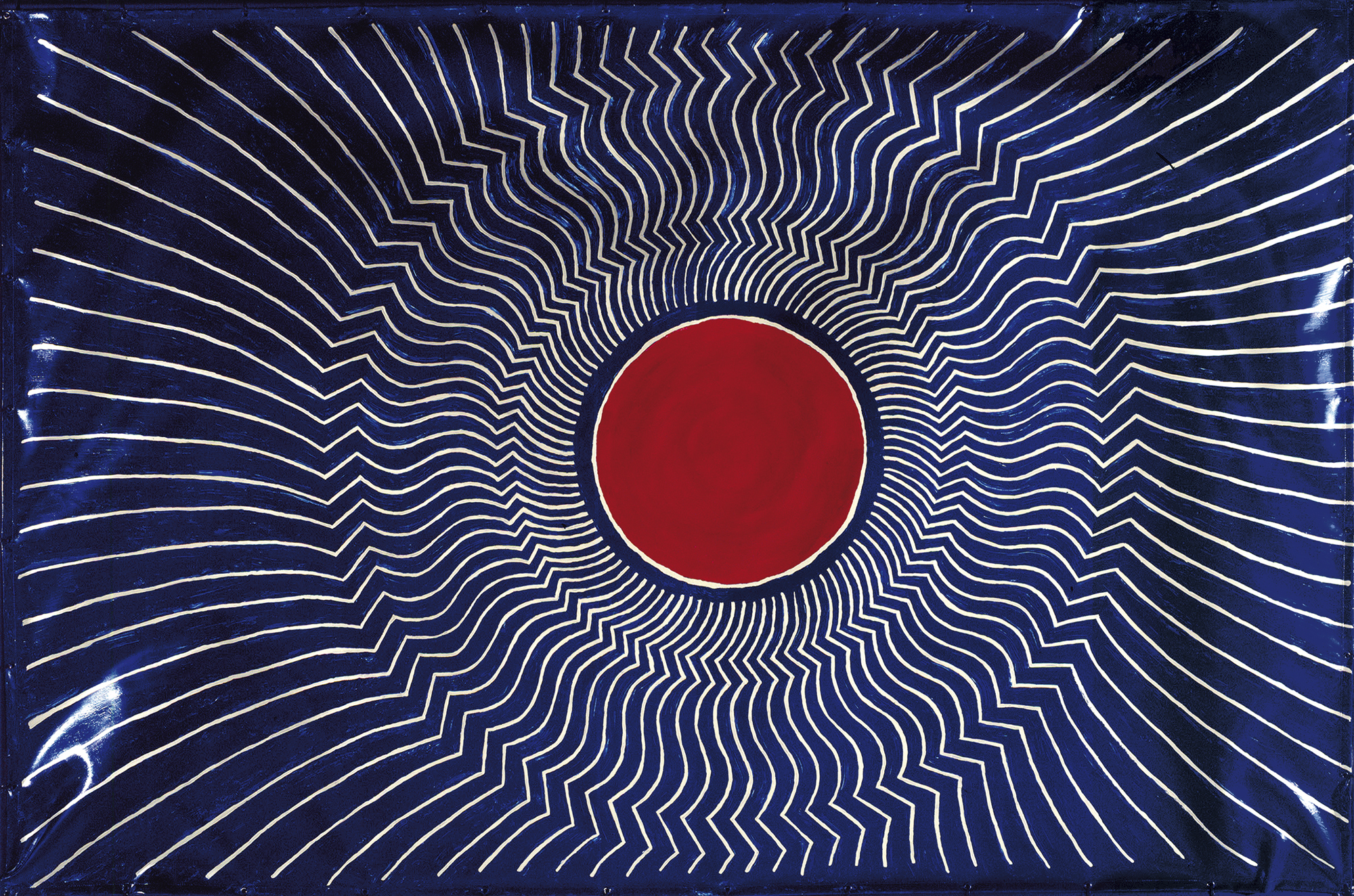

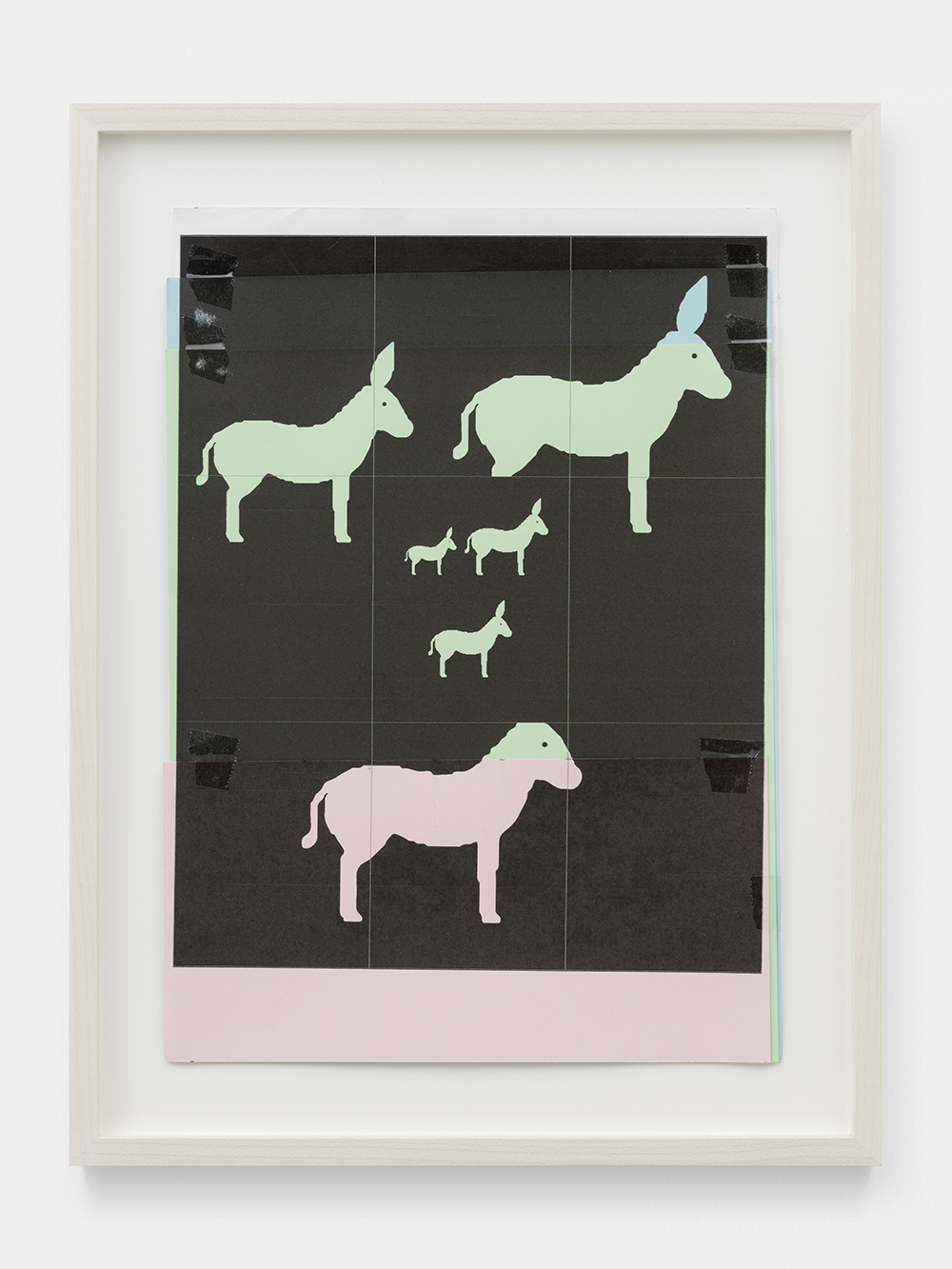

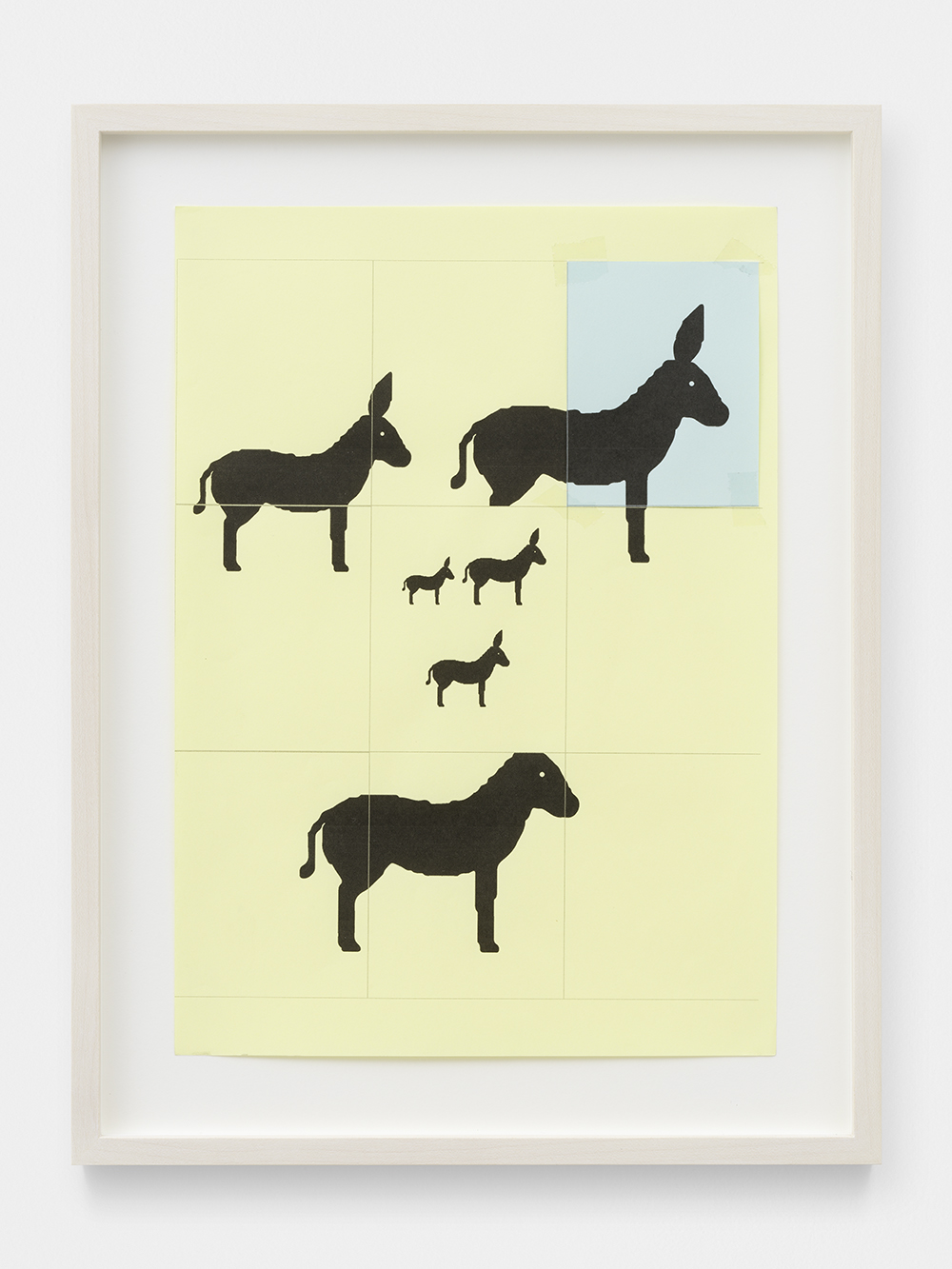

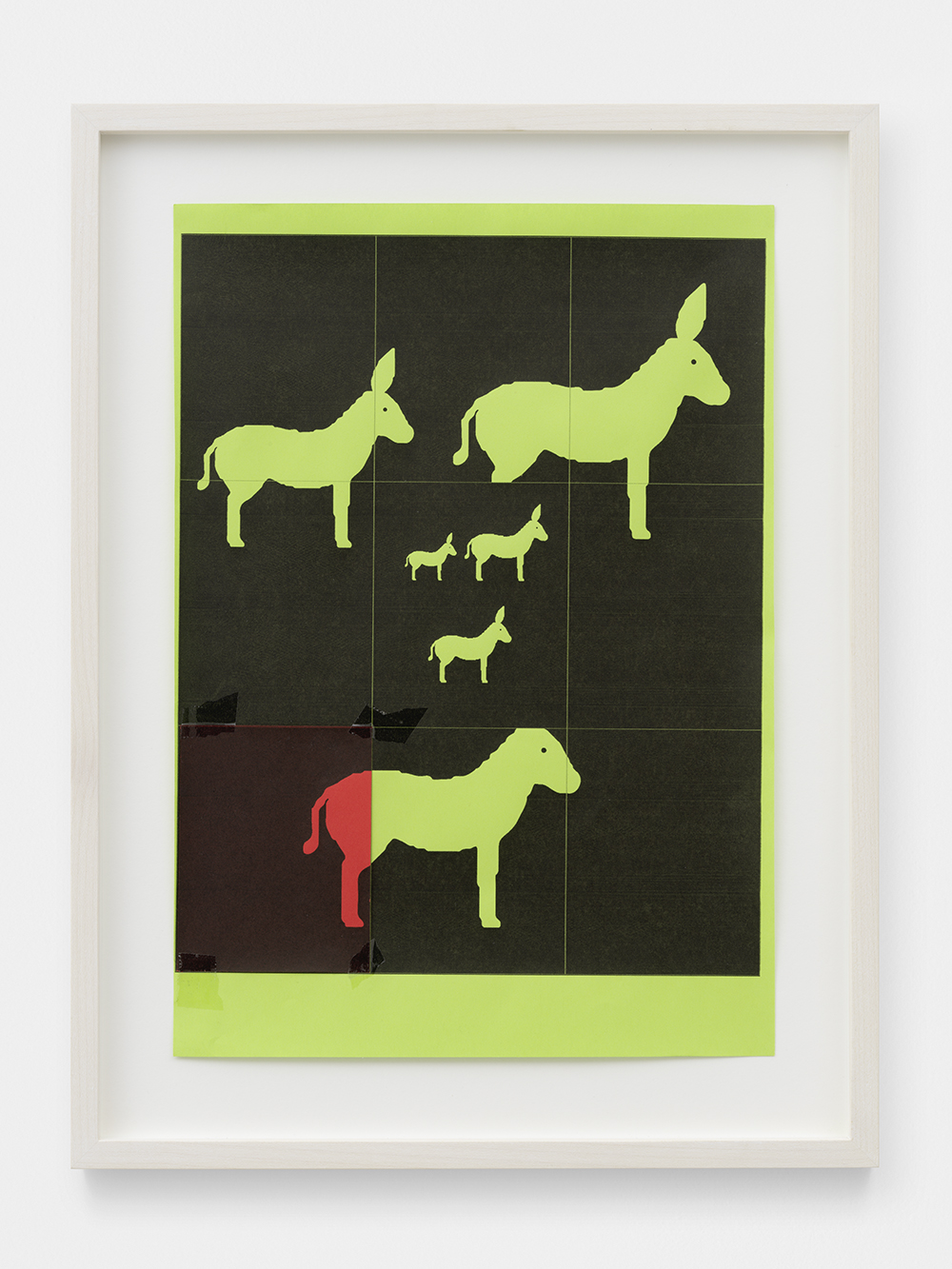

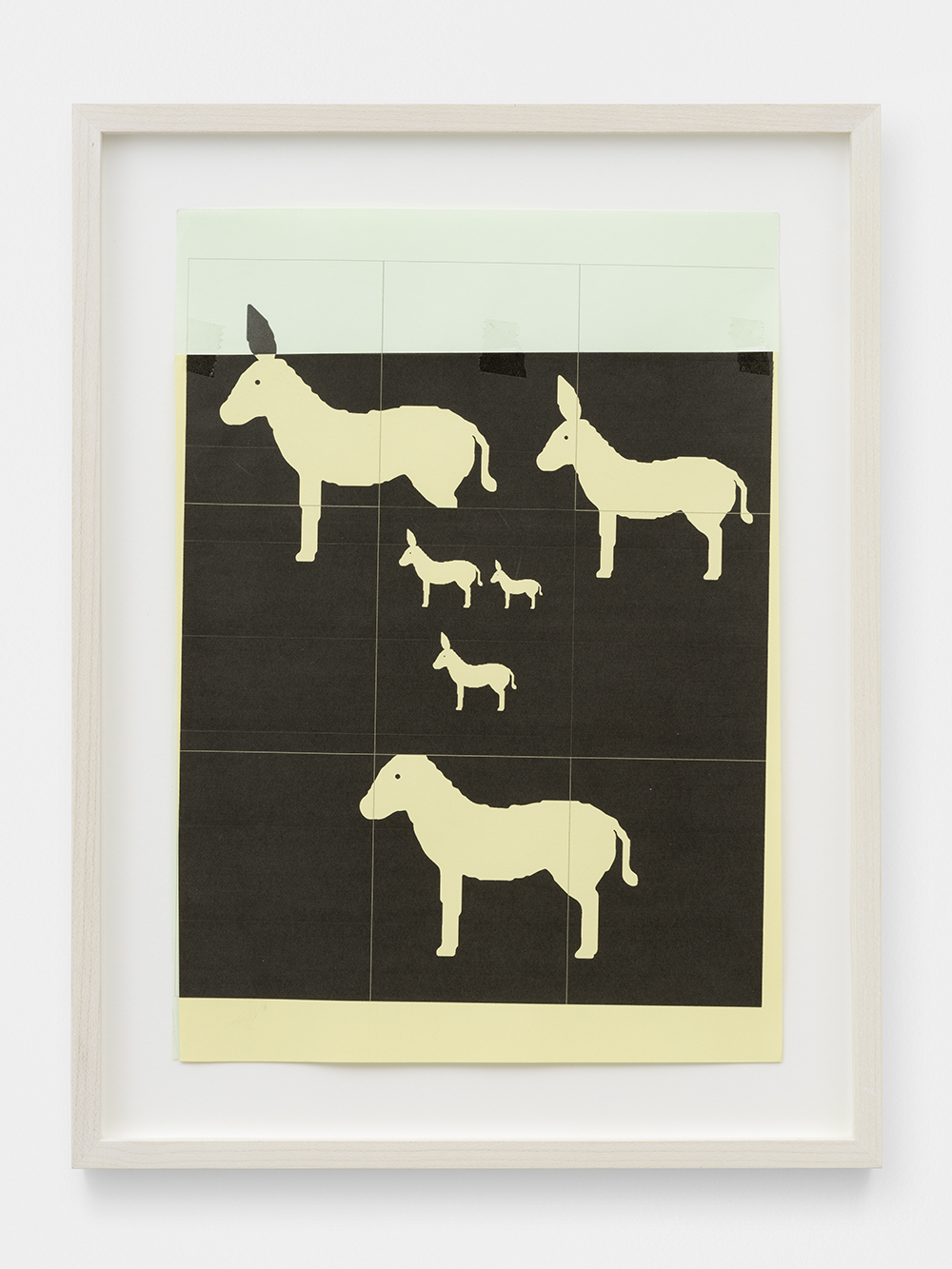

A native of Valais, where he currently lives and works, Carron reappropriates, copies and diverts from their normal context or use objects that are part of Valaisan culture and often deemed an embodiment of a certain Swiss identity. He creates replicas in synthetic materials like polyester or fibre glass, in imitation of wood, concrete and bronze. In this way, Carron both plays with the notion of authenticity and questions the weight of tradition and the values that attach to certain cultural products. By turning out numbers of the crosses seen in Valais at the top of calvaries and placing them in new and different contexts, he fuses the myth of a Switzerland of chalets and mountains with a spare, pared-down aesthetic, renewing the appropriationist strategies of American artists from the 1970s.

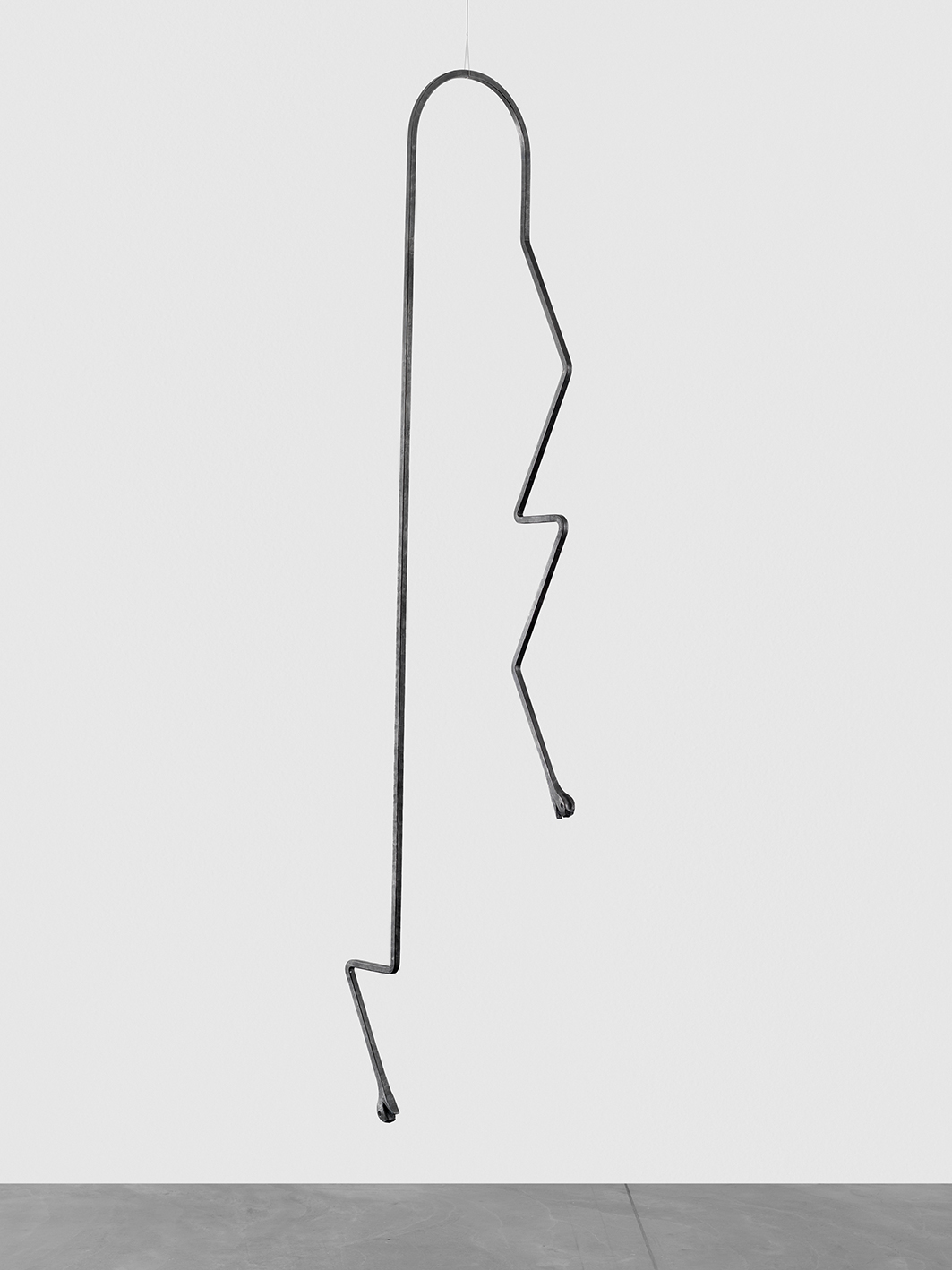

Carron also underscores the construction of Switzerland as a nation around a reinvented, often falsified folklore. Indeed, certain traditions recognised as historical were in fact only put together in the late 19th century, notably because of the need to forge a national identity. More recently, the artist has turned his attention to the field of art by reappropriating, almost as parody, the canvases of Fernand Léger and the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti. This reinterpretative work makes it possible to neutralise the position of authority that accrues to the piece of art, and suggests the idea of an art that partakes of popular culture.

Carron summons archetypes bound up with a folkloric, artistic or religious iconography; he does so with irony and detachment, but also in a critical spirit. His sculptures, more akin to pastiche than celebration, point up the machinery behind the set of symbols surrounding the product of any human endeavour.

A native of Valais, where he currently lives and works, Carron reappropriates, copies and diverts from their normal context or use objects that are part of Valaisan culture and often deemed an embodiment of a certain Swiss identity. He creates replicas in synthetic materials like polyester or fibre glass, in imitation of wood, concrete and bronze. In this way, Carron both plays with the notion of authenticity and questions the weight of tradition and the values that attach to certain cultural products. By turning out numbers of the crosses seen in Valais at the top of calvaries and placing them in new and different contexts, he fuses the myth of a Switzerland of chalets and mountains with a spare, pared-down aesthetic, renewing the appropriationist strategies of American artists from the 1970s.

Carron also underscores the construction of Switzerland as a nation around a reinvented, often falsified folklore. Indeed, certain traditions recognised as historical were in fact only put together in the late 19th century, notably because of the need to forge a national identity. More recently, the artist has turned his attention to the field of art by reappropriating, almost as parody, the canvases of Fernand Léger and the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti. This reinterpretative work makes it possible to neutralise the position of authority that accrues to the piece of art, and suggests the idea of an art that partakes of popular culture.

Carron summons archetypes bound up with a folkloric, artistic or religious iconography; he does so with irony and detachment, but also in a critical spirit. His sculptures, more akin to pastiche than celebration, point up the machinery behind the set of symbols surrounding the product of any human endeavour.