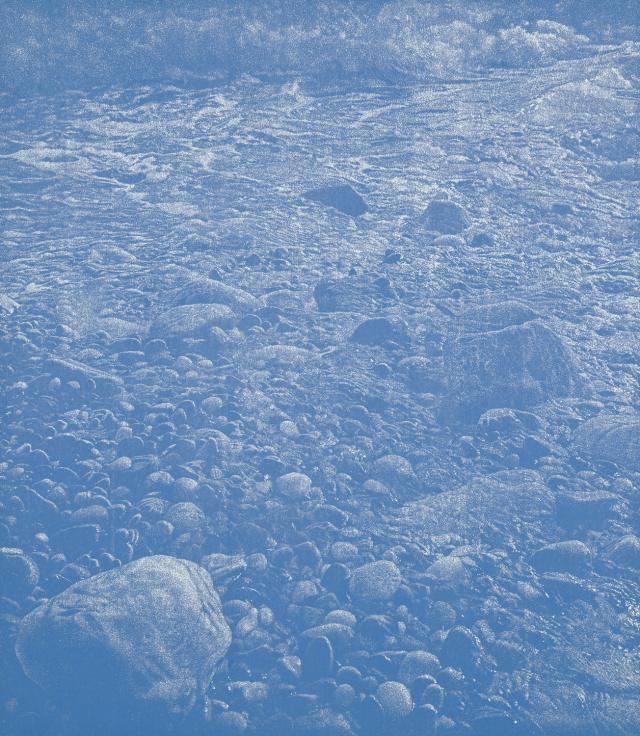

Cima del Mar and Gräser II are two prints resulting from the woodcut process, favoured by Franz Gertsch from 1986. The Bern-based artist updates, from an unusual angle, the ancestral technique of piquage which consists of piercing a wooden plate with tiny incisions in a more or less dense network, so as to make the subject appear through the progressive subtraction of material. The artist works in darkness from a photographic image projected on a fine sheet of wood, painted beforehand with a strong colour, so that the appearance of the motif is visible.

The undertaking, which led to the edition of huge sheets of Japanese paper specially produced by a master in Kyoto, Ivano Heizaburo, assumed an exceptional character because it in fact required several months of work on the wooden plate, which then extended to a process of manual printing, as equally long and meticulous. Each of the two woodcuts here depicts an extract from nature, tightly framed, attracting the eye to the composition’s details. River, stones and vegetation fill the space initially carved into the wood before being set on paper. The reduction of the motif and of the narration leaves room for intense contemplation. Each print is printed in a single tone, composed of one to two colours.

Here photography merely represents the point of departure of a creative process whereas the actual technique of the woodcut breaks with the idea of the snapshot. Gräser II and Cima del Mar reflect back to the spectator the image of an image in which the time needed for their creation is embodied. Dissected into a myriad of tiny grooves, the artist thus dematerialises the subject as object and pushes the motif’s resistance against the abstraction away. Franz Gertsch has never been content to simply reproduce nature; on the contrary, his approach attempts to attract the gaze to a new reality. By rendering the detail so monumentally, the artist captures time in the instant and offers a pictorial interpretation inducing meditation. Gertsch’s woodcut oeuvre offers a feeling of universality through the transgression of temporality. In the era of technical reproducibility, the artist restores the lost aura foretold by Walter Benjamin in 1936.

The undertaking, which led to the edition of huge sheets of Japanese paper specially produced by a master in Kyoto, Ivano Heizaburo, assumed an exceptional character because it in fact required several months of work on the wooden plate, which then extended to a process of manual printing, as equally long and meticulous. Each of the two woodcuts here depicts an extract from nature, tightly framed, attracting the eye to the composition’s details. River, stones and vegetation fill the space initially carved into the wood before being set on paper. The reduction of the motif and of the narration leaves room for intense contemplation. Each print is printed in a single tone, composed of one to two colours.

Here photography merely represents the point of departure of a creative process whereas the actual technique of the woodcut breaks with the idea of the snapshot. Gräser II and Cima del Mar reflect back to the spectator the image of an image in which the time needed for their creation is embodied. Dissected into a myriad of tiny grooves, the artist thus dematerialises the subject as object and pushes the motif’s resistance against the abstraction away. Franz Gertsch has never been content to simply reproduce nature; on the contrary, his approach attempts to attract the gaze to a new reality. By rendering the detail so monumentally, the artist captures time in the instant and offers a pictorial interpretation inducing meditation. Gertsch’s woodcut oeuvre offers a feeling of universality through the transgression of temporality. In the era of technical reproducibility, the artist restores the lost aura foretold by Walter Benjamin in 1936.