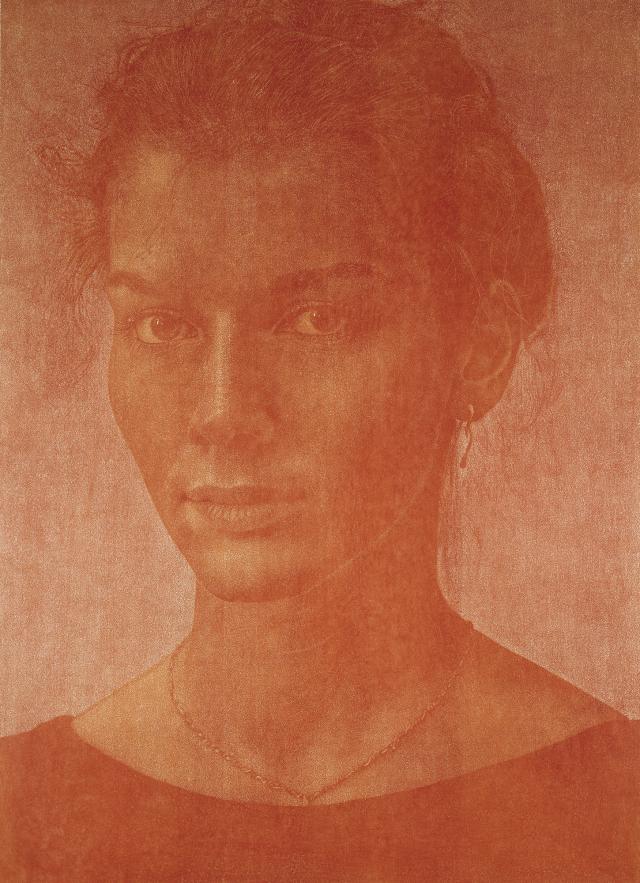

Franz Gertsch created Doris in 1989, three years after having completed Natascha II, his first woodcut portrait. The portrait, often of monumental dimensions, is a genre Gertsch has been fond of since the beginnings of his hyperrealist painting and something he favours in different techniques. To achieve the specific tone of this print, Gertsch successively printed three hues on the same sheet of paper: a dark red, a pale, almost transparent red and a warmly toned yellow which only covers the face’s silhouette. The uniform application of colour, the meticulous setting up of the template form on the previous print, as well as the delicate manipulation of the paper, required the assistance of several people. Printing only once each colour, Gertsch makes each of Doris’s eighteen prints unique.

The virtuosity of the gesture is expressed in the conjunction between the complexity of the process and the detail of the image. The time needed for the artist to be able to make the contours of each eyelash, each strand of hair and each reflection plunges the spectator into a contemplative state. This work relates more to a manifestation than to the genuine reproduction of the visible, and it opens up new dimensions to traditional technique, brushing aside the boundaries of drawing and paper. When he started his woodcut process, Gertsch was able to produce larger formats than those permitted by the photography of the period. It was a way for him to pay homage to the sixth art, which he had employed since the beginnings of his photorealist painting. The instantaneousness of the snapshot enabled him to immobilise his subjects in the moment of the reproduction, followed by that of the observation.

Through the close up, Gertsch appropriates the faces of his models to give life to matter. He was particularly interested in characters portraying emerging creative artists, in a moment of transition between adolescence and adult life, frequently with an androgynous side. His portrayal of Patti Smith provides an equally authentic vision as the self-portraits which he undertook from 1980 on. His work continues to be on a monumental scale, imparting an iconic dimension to his subjects. When one approaches the hatched surface, the accumulation of tiny incisions itself allows the modelling of the image. Franz Gertsch’s approach rebels against speed, the snapshot and the virtual, to better anchor his oeuvre in a universal timelessness.

The virtuosity of the gesture is expressed in the conjunction between the complexity of the process and the detail of the image. The time needed for the artist to be able to make the contours of each eyelash, each strand of hair and each reflection plunges the spectator into a contemplative state. This work relates more to a manifestation than to the genuine reproduction of the visible, and it opens up new dimensions to traditional technique, brushing aside the boundaries of drawing and paper. When he started his woodcut process, Gertsch was able to produce larger formats than those permitted by the photography of the period. It was a way for him to pay homage to the sixth art, which he had employed since the beginnings of his photorealist painting. The instantaneousness of the snapshot enabled him to immobilise his subjects in the moment of the reproduction, followed by that of the observation.

Through the close up, Gertsch appropriates the faces of his models to give life to matter. He was particularly interested in characters portraying emerging creative artists, in a moment of transition between adolescence and adult life, frequently with an androgynous side. His portrayal of Patti Smith provides an equally authentic vision as the self-portraits which he undertook from 1980 on. His work continues to be on a monumental scale, imparting an iconic dimension to his subjects. When one approaches the hatched surface, the accumulation of tiny incisions itself allows the modelling of the image. Franz Gertsch’s approach rebels against speed, the snapshot and the virtual, to better anchor his oeuvre in a universal timelessness.