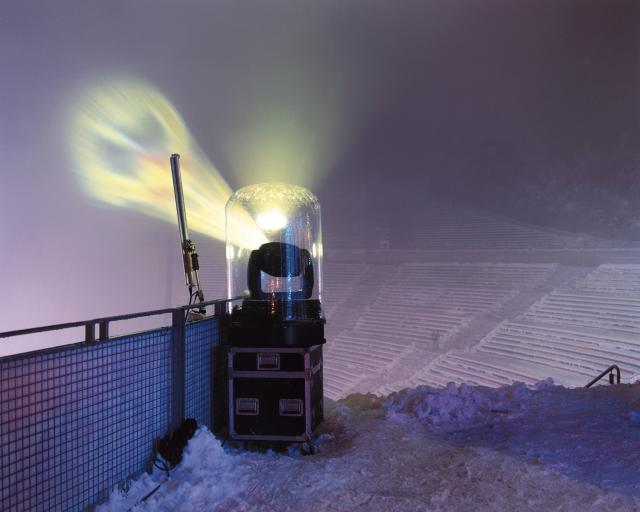

Jules Spinatsch began his Snow Management cycle in 2001. Over a period of several years, the artist constructed a constellation of carefully choreographed images that were subtly differentiated by the multiplicity of viewpoints adopted. Made up exclusively of night photographs, the series immortalises the process of transforming a winter landscape in an alpine region, employing images that record the preparations of the ski trails. The sole protagonists of this spectacle of an utterly prefabricated mise en scène are the snow cannons working at full throttle, the backhoes, and the snowcats grooming the trails under the spotlights. Their cold artificial light generates powerful chiaroscuro effects with virtual highlights, likening this bit of nature “in production” to the apocalyptic vision of a frozen and sterile lunar landscape.

These pictures show us the final stage of development imposed by a contemporary tourism industry in the grip of market forces, i.e., adapting the landscape to the demand and requirements of the clientele for winter sports, and hence subjecting it to the dictates of consumer society. Far from the heavenly images of the Alps’ snow-capped peaks, which first began celebrating the sumptuousness of a still-intact nature in the 18th century, Spinatsch has chosen to reveal a vulnerable environment, tamed by man and subjected to his perpetual dissatisfaction. Here he paints the tourism industry as an instrumentalised system extolling the beauty of this virgin nature in a typically romantic spirit while never missing a chance to capitalise on the myth, at the risk of threatening the long-term future of this wild landscape.

The raw aestheticism of these highly frontal photographs inevitably gives voice to a feeling of unease with respect to the power exercised by the “snow economy,” which over the years has converted part of the Alps into an immense leisure park, a high-tech landscape for special events directed toward the maximisation of profits. Producing once again images that are far from what we are used to seeing, and choosing anew to show what is going on behind the scenes, Spinatsch looks to shake up our perception of “reality” by letting us in on the secret ingredients of a well-kept recipe.

These pictures show us the final stage of development imposed by a contemporary tourism industry in the grip of market forces, i.e., adapting the landscape to the demand and requirements of the clientele for winter sports, and hence subjecting it to the dictates of consumer society. Far from the heavenly images of the Alps’ snow-capped peaks, which first began celebrating the sumptuousness of a still-intact nature in the 18th century, Spinatsch has chosen to reveal a vulnerable environment, tamed by man and subjected to his perpetual dissatisfaction. Here he paints the tourism industry as an instrumentalised system extolling the beauty of this virgin nature in a typically romantic spirit while never missing a chance to capitalise on the myth, at the risk of threatening the long-term future of this wild landscape.

The raw aestheticism of these highly frontal photographs inevitably gives voice to a feeling of unease with respect to the power exercised by the “snow economy,” which over the years has converted part of the Alps into an immense leisure park, a high-tech landscape for special events directed toward the maximisation of profits. Producing once again images that are far from what we are used to seeing, and choosing anew to show what is going on behind the scenes, Spinatsch looks to shake up our perception of “reality” by letting us in on the secret ingredients of a well-kept recipe.