Since 1992, the clown has been a key figure in the oeuvre of Ugo Rondinone, who began his career by regularly disguising himself as this whimsical and highly colourful character. The artist’s alter ego, it then continued to make constant appearances in his performances, installations, videos and Polaroids, as well as in wax, life-size sculptures. As Rondinone points out, the clown finds its origins in the buffoon figure, which was a pure invention of the nobility destined to make up for the boredom and gloom of the court. Its role is to constantly entertain an insatiable and ravenous public.

Other 20th century artists, such as Roni Horn, Maurizio Cattelan and Cindy Sherman, have also appropriated the clown figure and its metaphorical self-representation potential. But in Rondinone’s work, little by little, the clown figure seems to have been used as a means to express a melancholic feeling with regard to the loss of what may be creative freedom. Although it initially appeared full of energy and humour, it has progressively been depicted as sad, with a downcast and exhausted air. It has materialised into a chubby mannequin slumped on the floor, lethargic and worn out. Disconnected from its usual references, spectators experience a feeling of discomfort in front of this still and silent figure, as though their own presence had become obsolete and useless because the show seems to be over.

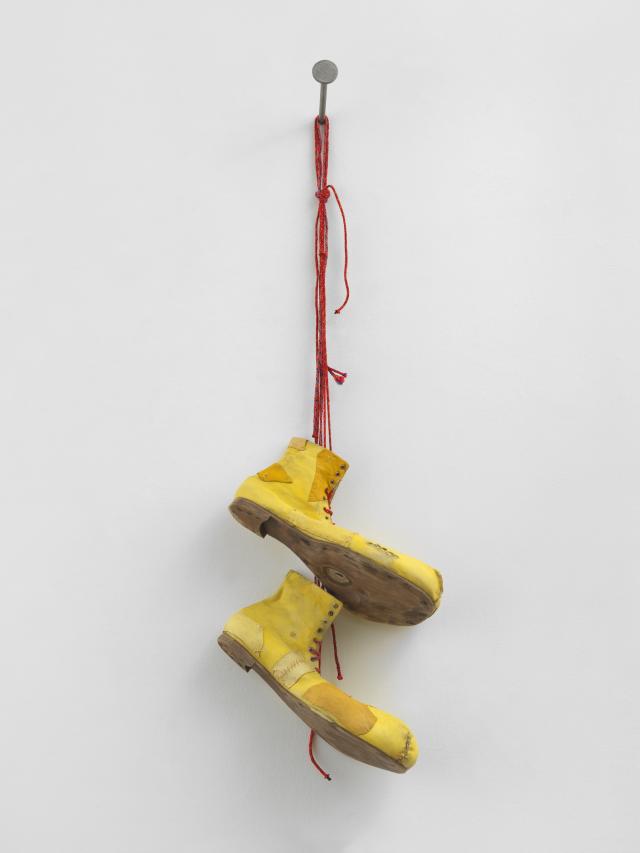

Tired of making the crowd laugh, the afflicted clown not only functions as an effigy of the modern artist and his tragic destiny of having to entertain the public, but also allows Rondinone to evoke in a more general way the unabashed refusal to respond to the desires and expectations of others. In still, the clown has removed his worn out clodhoppers and left them in the changing room. He creates a disturbance and keeps us in suspense. Will he return or has he left for good?

Other 20th century artists, such as Roni Horn, Maurizio Cattelan and Cindy Sherman, have also appropriated the clown figure and its metaphorical self-representation potential. But in Rondinone’s work, little by little, the clown figure seems to have been used as a means to express a melancholic feeling with regard to the loss of what may be creative freedom. Although it initially appeared full of energy and humour, it has progressively been depicted as sad, with a downcast and exhausted air. It has materialised into a chubby mannequin slumped on the floor, lethargic and worn out. Disconnected from its usual references, spectators experience a feeling of discomfort in front of this still and silent figure, as though their own presence had become obsolete and useless because the show seems to be over.

Tired of making the crowd laugh, the afflicted clown not only functions as an effigy of the modern artist and his tragic destiny of having to entertain the public, but also allows Rondinone to evoke in a more general way the unabashed refusal to respond to the desires and expectations of others. In still, the clown has removed his worn out clodhoppers and left them in the changing room. He creates a disturbance and keeps us in suspense. Will he return or has he left for good?