In the autumn of 2010, Jules Spinatsch displayed on Karlsplatz in Vienna a photographic panorama of the Viennese Opera Ball that measured thirty-five metres long by three metres high and was installed around a 360-degree rotunda. While at first sight it gave the impression of being continuous, the panorama was in fact made up of 17,352 individual images that had been recorded by two programmed remote-controlled security cameras throughout the evening (from 8:32 pm to 5:17 am) at regular three-second intervals in a space-sweeping movement.

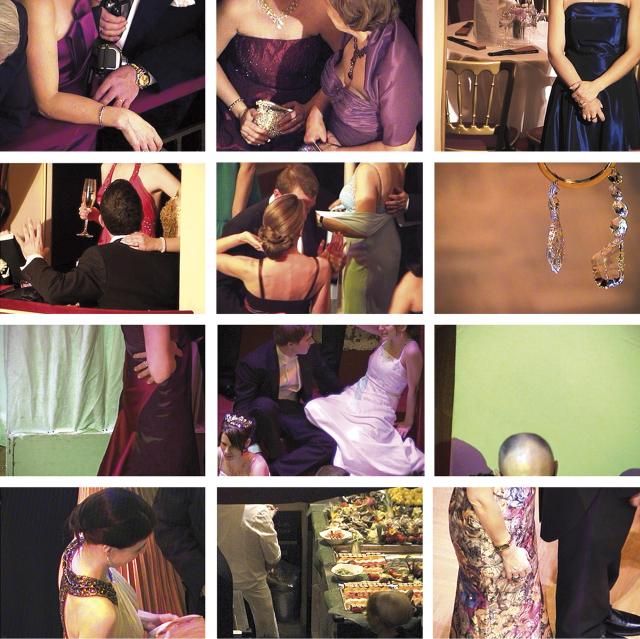

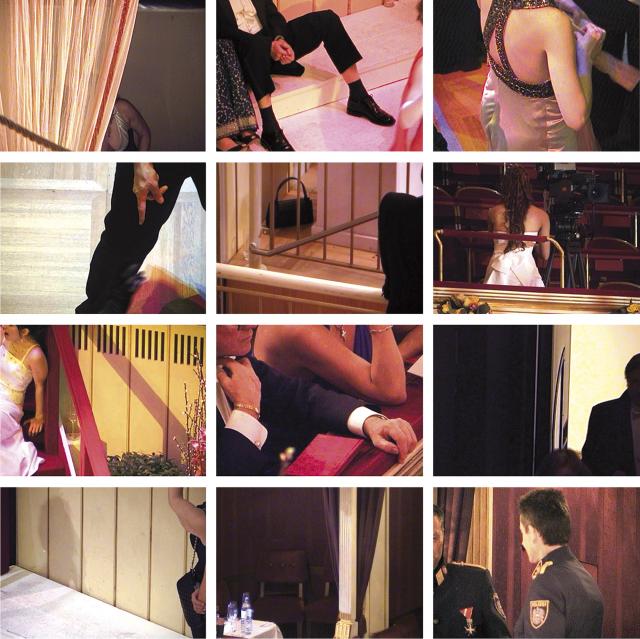

From this vast chronological repertory of photos transcribing the event down to the least detail, Spinatsch selected out several series of works, vibrant mosaics of disparate moments. Revealing the festive charms of this grand ball and rite of passage with its outdated atmosphere, the 120 photographic fragments making up Bloc Les Illustres show scenes that are banal but also odd and above all stolen without the knowledge of their subjects. Photographed candidly from life, they are seen letting themselves go, striking the most relaxed or mischievous poses between a narcissistic control of their appearance and utter obliviousness.

Long silk dresses, bow ties, diamond jewellery, formal attire, hair done in graceful buns, and tail coats flitter in the balconies and parade about amidst the gilt, the sheen and the velvet of the sumptuous setting. Elsewhere the guests seem tired, weary, exhausted by the long evening’s festivities. Taken with other images mixed in and showing the technical equipment of the ballroom, its decorations and lighting, these anonymous figures compose a Hitchcockian plot of captivating suspense and multiple possibilities. Hunting around for bits of narrative, viewers become intrusive voyeurs in the wings of an especially prized spectacle, one that is still deemed today the most important gathering of the Austrian elite. But Spinatsch’s project reveals an unexpected dimension of this highly codified context, when the actors drop their masks and their poses become much freer and uninhibited.

The artist highlights the omnipresence of tools that are supposed to work to ensure our security and which capture each of our movements, drastically reducing our right to privacy and to be alone. The protagonists of the ball form a sweeping fresco of the human comedy that blends power games and seduction, the pomp of wealth, voyeurism and current obsessions about security. Timeless, the picture is both stuck in a past that comes flooding back for the occasion, and totally contemporary in its fragmented composition of multiple random views, which ironically put one in mind of the pixels making up digital photographs today.

From this vast chronological repertory of photos transcribing the event down to the least detail, Spinatsch selected out several series of works, vibrant mosaics of disparate moments. Revealing the festive charms of this grand ball and rite of passage with its outdated atmosphere, the 120 photographic fragments making up Bloc Les Illustres show scenes that are banal but also odd and above all stolen without the knowledge of their subjects. Photographed candidly from life, they are seen letting themselves go, striking the most relaxed or mischievous poses between a narcissistic control of their appearance and utter obliviousness.

Long silk dresses, bow ties, diamond jewellery, formal attire, hair done in graceful buns, and tail coats flitter in the balconies and parade about amidst the gilt, the sheen and the velvet of the sumptuous setting. Elsewhere the guests seem tired, weary, exhausted by the long evening’s festivities. Taken with other images mixed in and showing the technical equipment of the ballroom, its decorations and lighting, these anonymous figures compose a Hitchcockian plot of captivating suspense and multiple possibilities. Hunting around for bits of narrative, viewers become intrusive voyeurs in the wings of an especially prized spectacle, one that is still deemed today the most important gathering of the Austrian elite. But Spinatsch’s project reveals an unexpected dimension of this highly codified context, when the actors drop their masks and their poses become much freer and uninhibited.

The artist highlights the omnipresence of tools that are supposed to work to ensure our security and which capture each of our movements, drastically reducing our right to privacy and to be alone. The protagonists of the ball form a sweeping fresco of the human comedy that blends power games and seduction, the pomp of wealth, voyeurism and current obsessions about security. Timeless, the picture is both stuck in a past that comes flooding back for the occasion, and totally contemporary in its fragmented composition of multiple random views, which ironically put one in mind of the pixels making up digital photographs today.