Spectacular, imposing and long inaccessible, the Alps have provoked fascination for centuries. For Collection Pictet, this motif serves as a bridge linking the works of the past with those of the contemporary era, revealing considerable changes in the perception and representation of the Swiss landscape. A scientific interest in the alpine world was soon replaced by an aesthetic quest for the romantic sublime, and then by a genuine effort to express a national identity during the 19th century. The landscape later reclaimed its expressive power and its status as a pictorial image through the audacious chromatic experiments of the expressionists. Contemporary practices finally propelled landscape representation onto the difficult territory of a subtle play between appropriation and reinvention.

In the 18th and 19th centuries

Even though the history of the landscape dates back to the 15th century in the West (through the veduta system—mainly practiced in France), it was not until the 18th century that artists started to give special attention to it. Unlike his French predecessors, Caspar Wolf (1735-1783) did not content himself with treating the landscape as the background of a religious scene (through a small window within the painting), but raised the alpine motif to the rank of principal subject. In response to the growing curiosity that the Swiss public had developed with regard to the landscape following Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s writings and Albrecht von Haller’s poems, Wolf went on many journeys to paint studies of various sites in central Switzerland. His detailed representations of glaciers and vegetation reveal a scientific interest for the subject, although sometimes—in order to respond to the common image of the Alps—he would stylise the landscape after returning to his studio, adding storm clouds and lightening to his compositions.

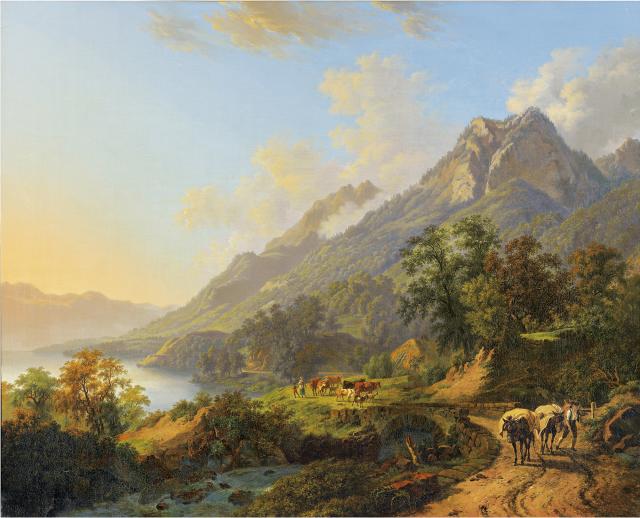

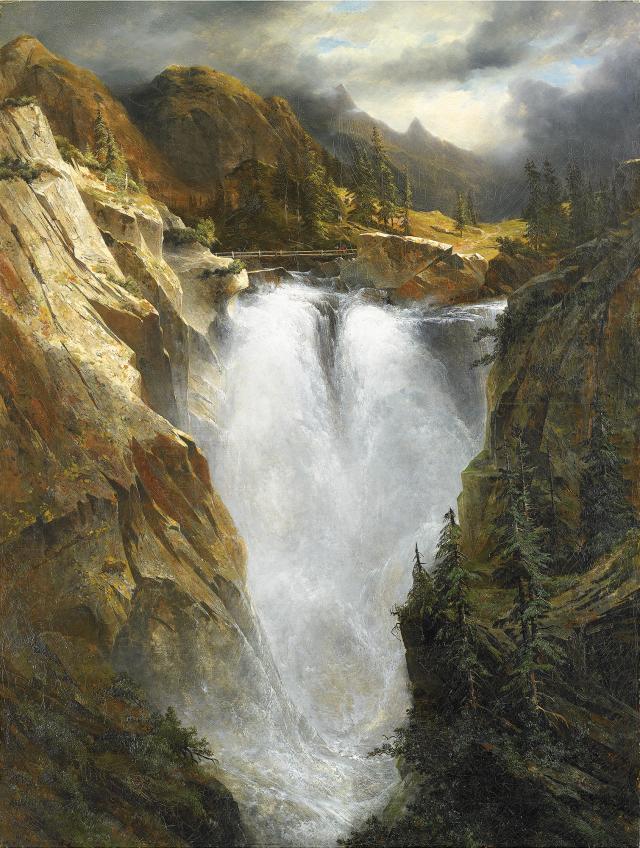

In search of the ideal of beautiful nature, Pierre-Louis De la Rive (1753-1817) aligned himself more closely with European Neoclassicism through the autonomous representation of mountains as a principal subject of the painting, although the desire to capture the natural sublime was coupled with a genuine concern for observation. The touch of François Diday (1802-1877), and later that of his disciple and rival in this area Alexandre Calame (1810-1864), refined landscape painting even more. In a style closer to romantic aesthetics, both Genevans contrasted Arcadian charm with the immeasurable power of wild nature. Their landscapes were grandiose and theatrical, while remaining faithful to the motif, subject to the desire to render nature’s turbulent spectacle in its most intense contrasts and plays of light.

Thanks to their work, Geneva became the birthplace of generations of artists specialising in the observation and depiction of mountain scenes, asserting itself as the foremost school of alpine painting. In the tumultuous political context of the establishment of the federal state in 1848, local painters attributed a special symbolism to the beauty of the Alps, linked to the crystallisation of a Swiss “national” spirit. The image of the alpine summits now served as a means of showing the unique identity of a new country within Europe.

In the 19th and 20th centuries

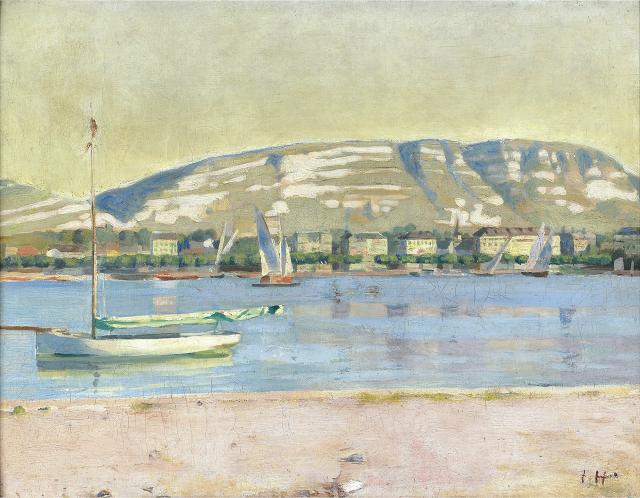

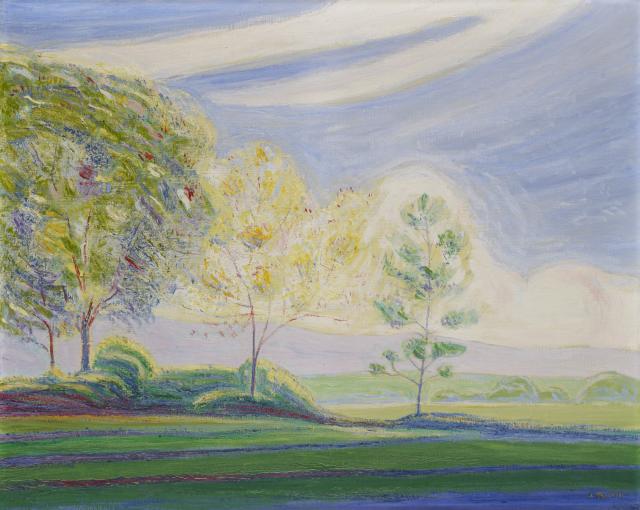

While contributing to the development of a Swiss artistic consciousness, Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) marked another turning point in the history of Swiss painting. The romantic sublime was henceforth asserted with the help of a repeated succession of landscape lines. In his effort to capture an immanent natural order, Hodler went beyond pure observation and turned the Swiss mountains into true icons. The horizontality of the layers in La Rade de Genève et le Salève prefigured his theory of parallelism and opened a pathway to a simpler, less heroic expression of nature, which was found again in the contemplative tranquillity of the paintings of Alexandre Perrier (1862-1936). Nevertheless, Perrier’s very fine, almost threadlike pointillist touch was strongly influenced by Parisian symbolism, and soon gave way to even more audacious forms of expression in the treatment of contrasts and contours.

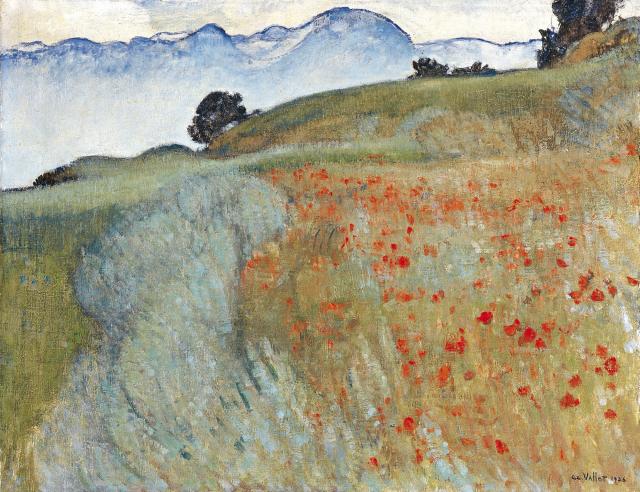

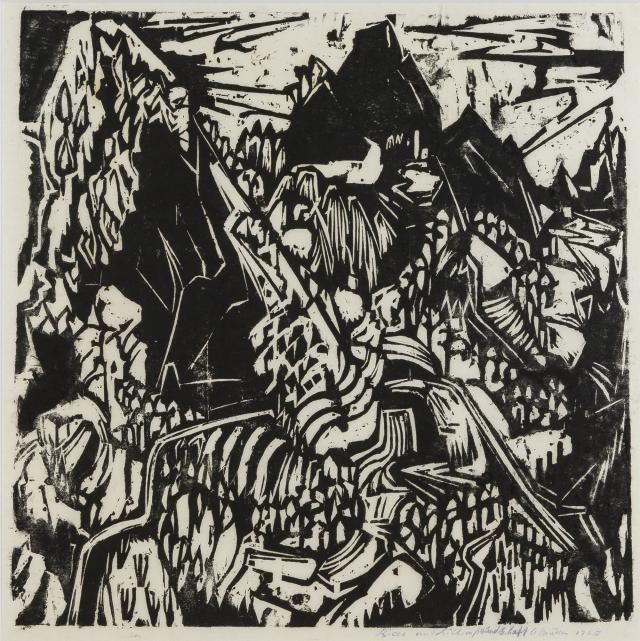

It was the concise shapes and sharp contrasts of Félix Vallotton (1865-1925) that brought Swiss art closer to the Parisian avant-garde. His black-and-white xylographs were unique for their visual power and economy of means. All detail was eliminated in favour of strong contrasts, which were also found in his oils on canvas and in his play with masses of colour. Vallotton thus rid himself of all overly literal rendering of nature’s spectacle, opting to express an unreal landscape.

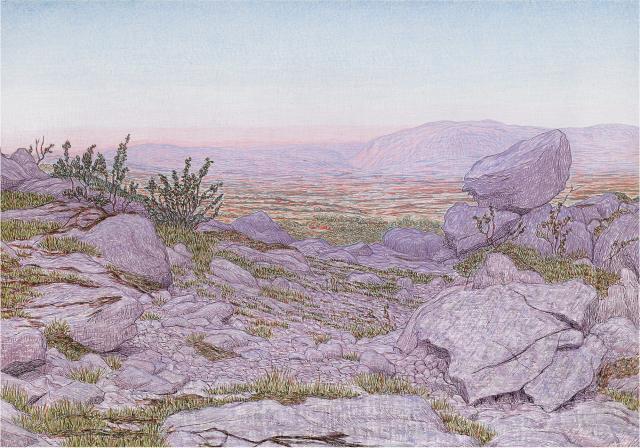

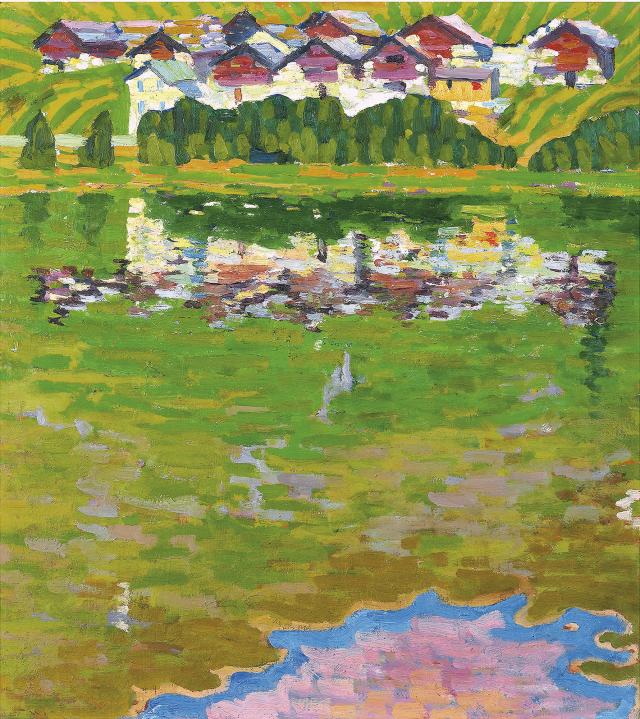

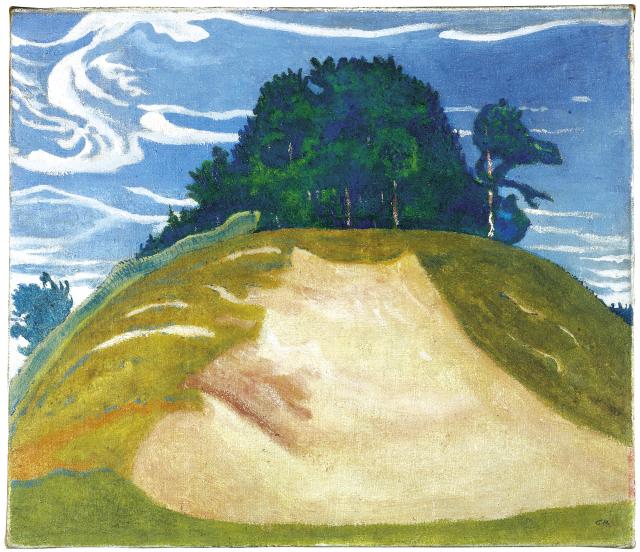

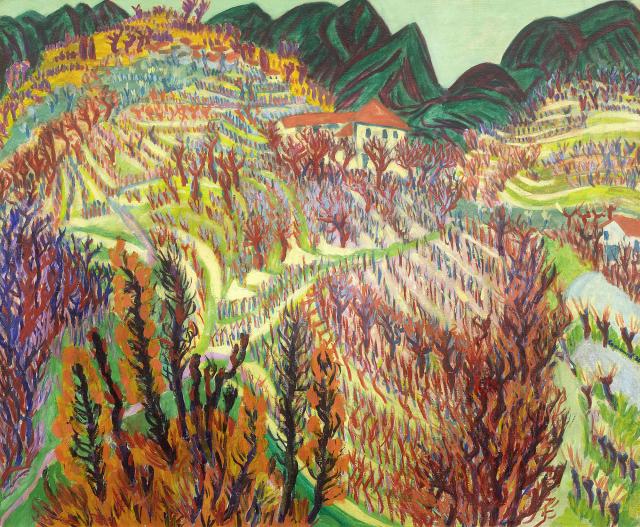

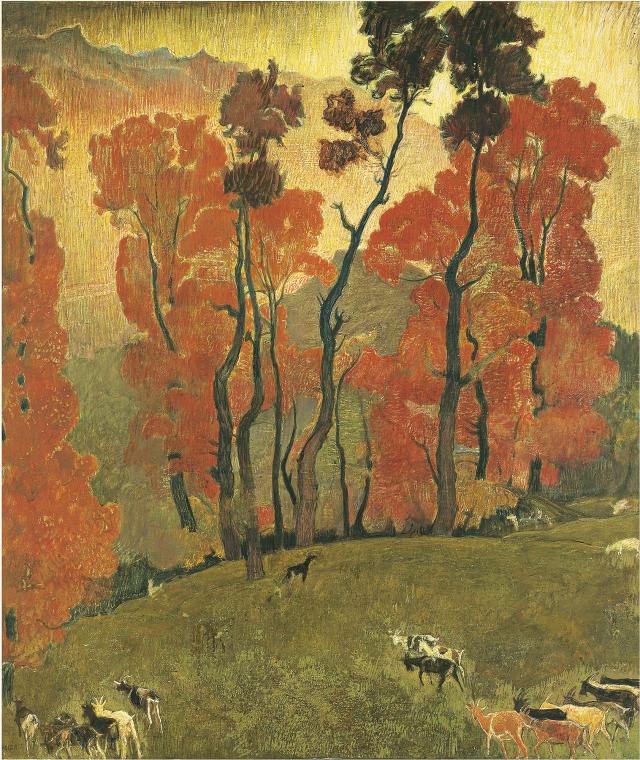

The chromatic research quest reached its apotheosis with Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933), Cuno Amiet (1868-1961) and Paul Camenisch (1893-1970), who extracted Swiss landscape painting from its regionalism once and for all, in order to make it part of an international art history. Amiet was strongly influenced by French Fauvism and was a member of the German expressionist group Die Brücke. He believed that “[...] the imitation of nature has no right to call itself a work of art”. Even without attaining abstraction, he dared to introduce audacious chromatic innovations in which colour proportioning and organisation sufficed for a composition. Camenisch’s acidic, surreal colours sketched troubling, haunting expressionist landscapes, while far from the major artistic centres, Giovanni Giacometti was adapting the influence of the avant-garde to the reality of the canton of Grisons. The landscape became a pretext for a play of colour and light. The viewer was no longer dealing with the image of a “mountain as mountain”, but with an image of the “mountain as painting”. If, at the beginning of the 19th century, landscape painting underwent a new phase of development due to the growth of tourism and professional mountain climbing, it would seem that at the end of the 19th century, it “gave the mountains back to art” in order to allow the alpine motif to assume a variety of forms in terms of technique and composition.

Although he used a palette of earthier tones, Édouard Vallet (1876-1929) also highlighted the expressive power of distinct pictorial layers, while Ernest Biéler (1863-1948) chose tempera to stylise natural motifs and encourage plays of transparency and colour in his representations of autumnal landscapes in the Savièse region.

Alice Bailly (1872-1938) had a different way of mining European avant-garde content, through a door to cubism and futurism. Convinced that “art is not a matter of skirts or trousers”, Bailly enthusiastically integrated the Parisian salons and embarked on an exploration of the geometry of shapes and visual rhythms. The paintings she created while staying in Switzerland during the Second World War display a true “colourful musicality”, thanks to their surprising, dreamlike, but always harmonious composition.