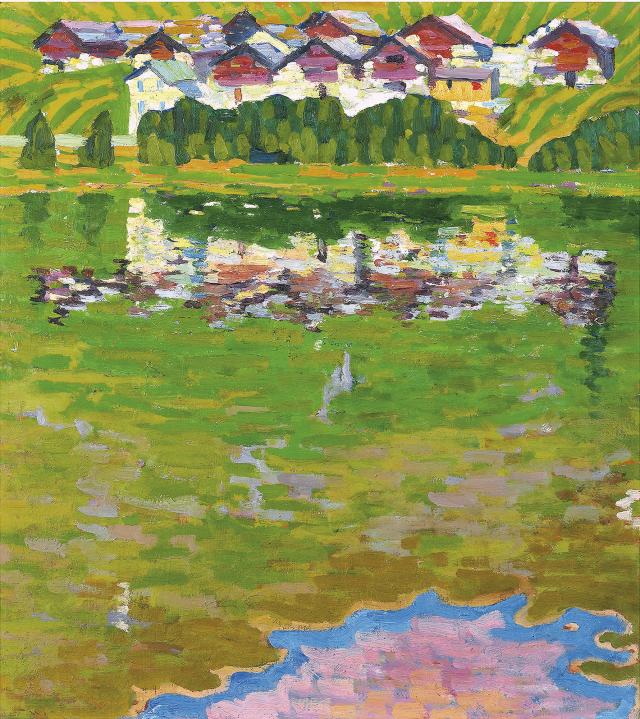

The bright colours and swift outlines that Swiss painter Cuno Amiet (1868-1961) used in the early 20th century resonated with the vitality, primitivism and vehemence of German expressionism, which had crystallised in the groups Die Brücke in Dresden and Der Blaue Reiter in Munich. In the vein of Vincent Van Gogh, James Ensor and Edvard Munch, the German expressionists were reacting (as were the French Fauvists) to impressionism, endeavouring to subjectively express the artist’s emotions in the face of reality, through saturated or acid colours, nervous lines, and occasionally caustic images that shocked viewers in search of harmony.

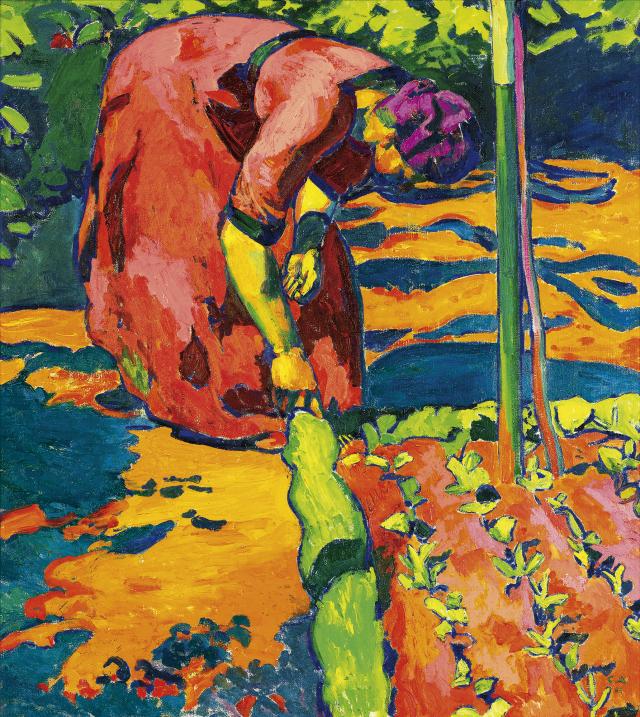

Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff—founders of the group Die Brücke—first noticed Amiet’s work during his 1905 exhibition at the Richter Gallery in Dresden. A short time later, they invited the Swiss artist to join them in their search for a new kind of artistic expressiveness, far removed from academic and bourgeois standards. From 1906 to 1913 in Switzerland, Amiet continued his unique chromatic experimentation as part of the German expressionist group, without imposing any restrictions on himself in terms of the techniques, themes and genres he chose to explore. Through landscapes, portraits, nudes and still lifes, he contributed to thrusting Swiss art into the heart of European modernism, while helping other Swiss artists make international connections, such as his friend Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933).

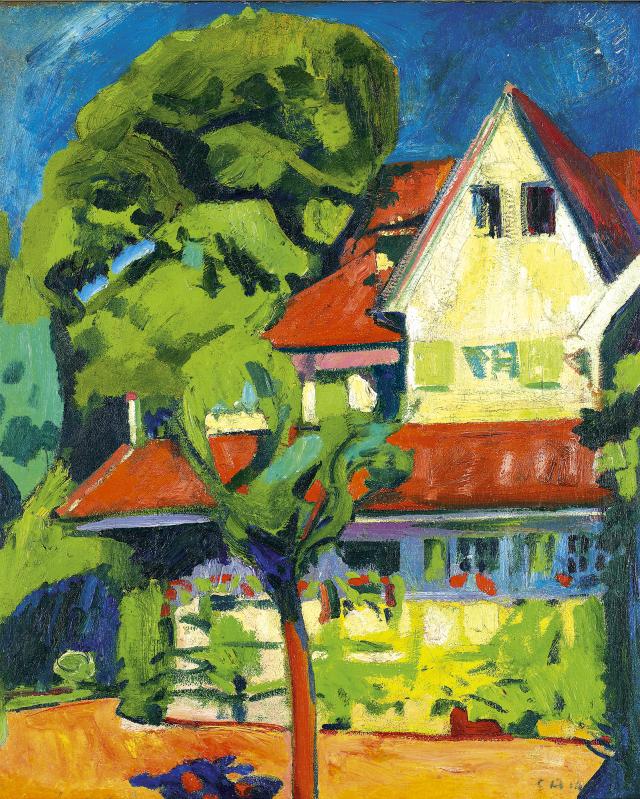

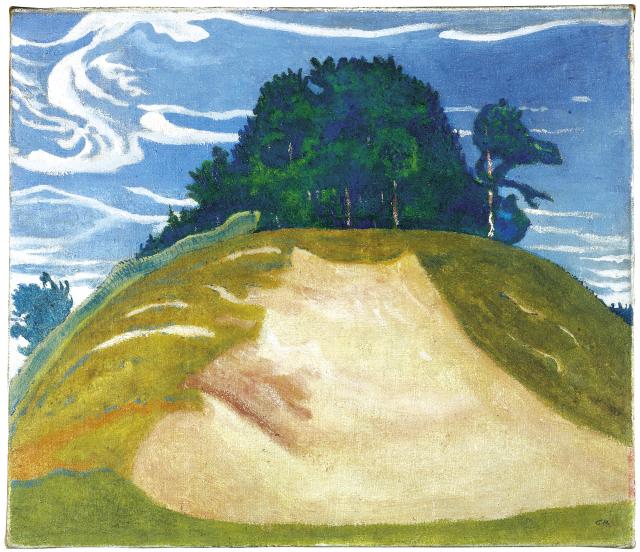

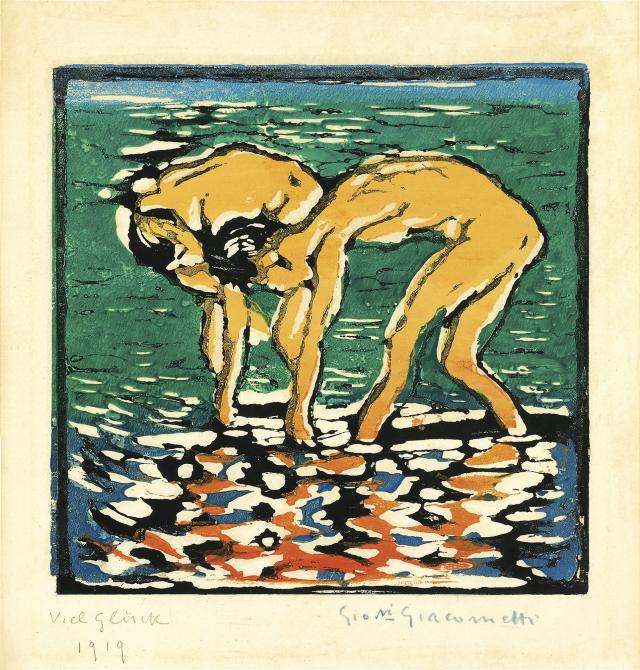

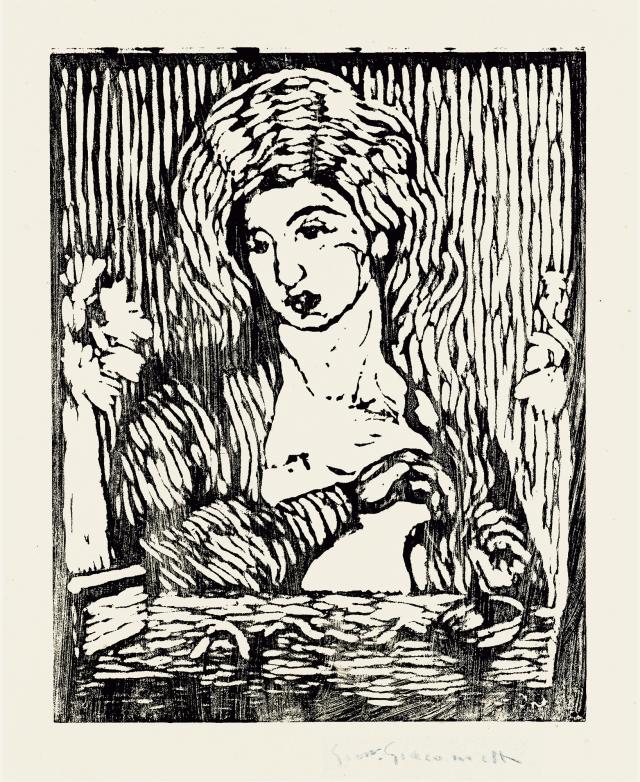

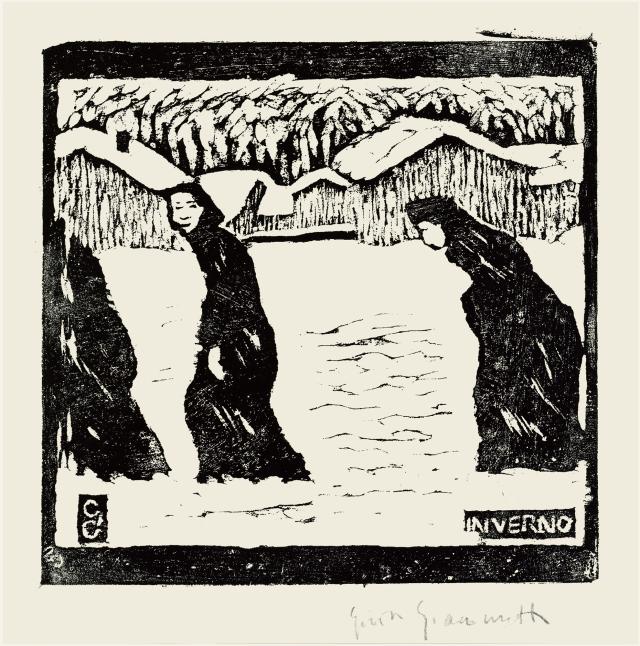

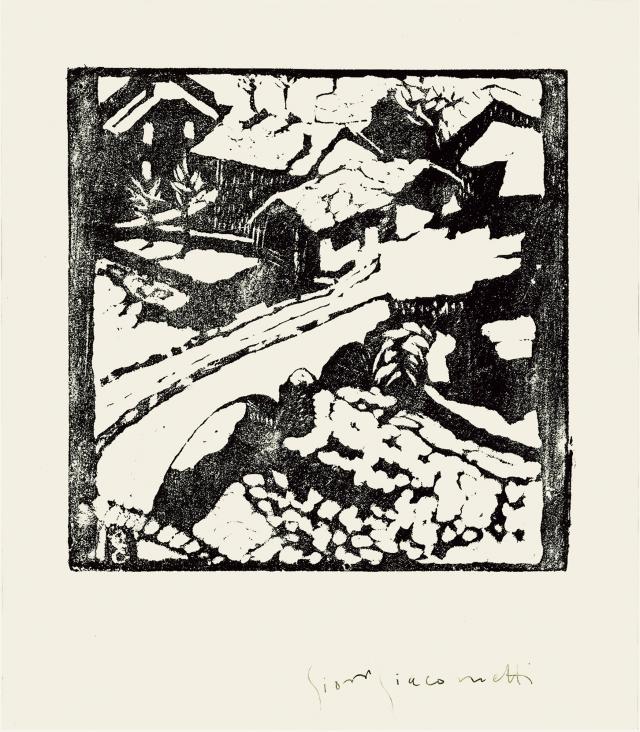

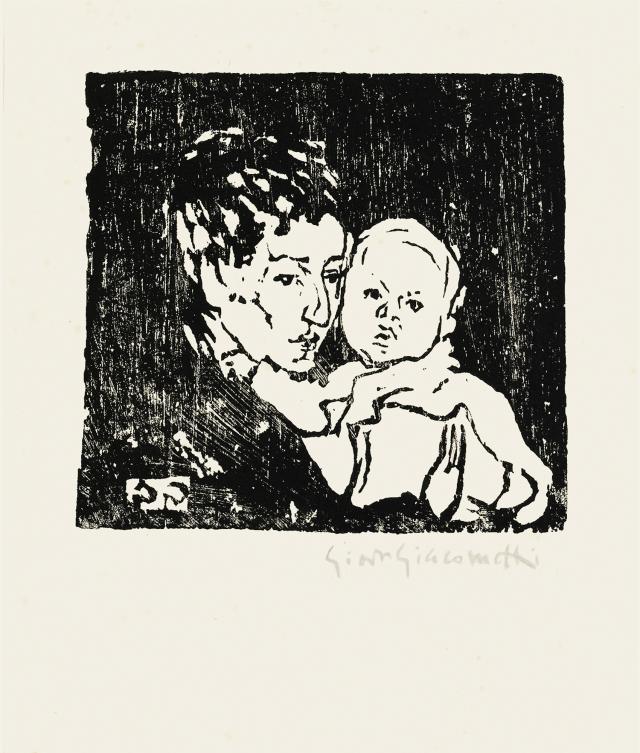

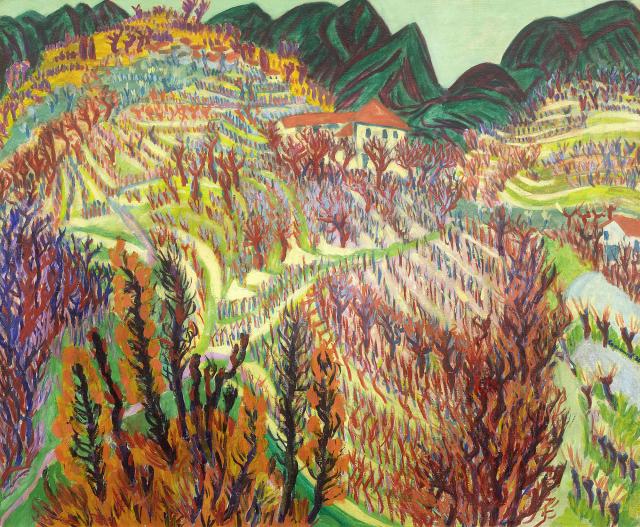

Without having officially joined the group, Giovanni Giacometti was deeply influenced by Die Brücke, with which was he closely associated from 1908. Giacometti developed and renewed the influence of the European avant-garde with his audacious palette, radiant orchestrations, and the angular lines of his wood engravings, while adapting these to the landscapes of Grisons.

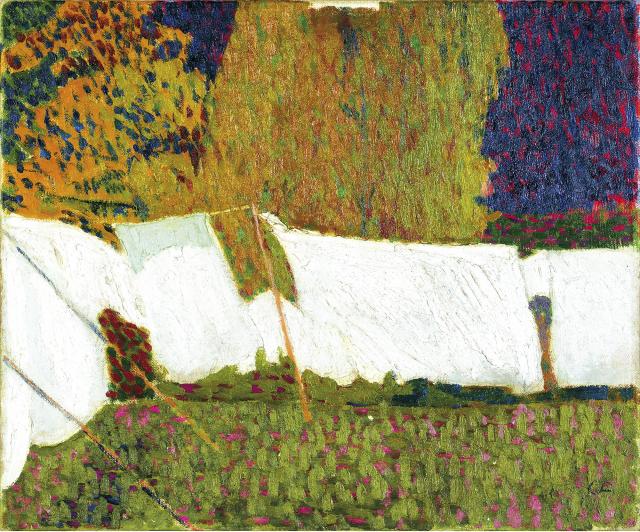

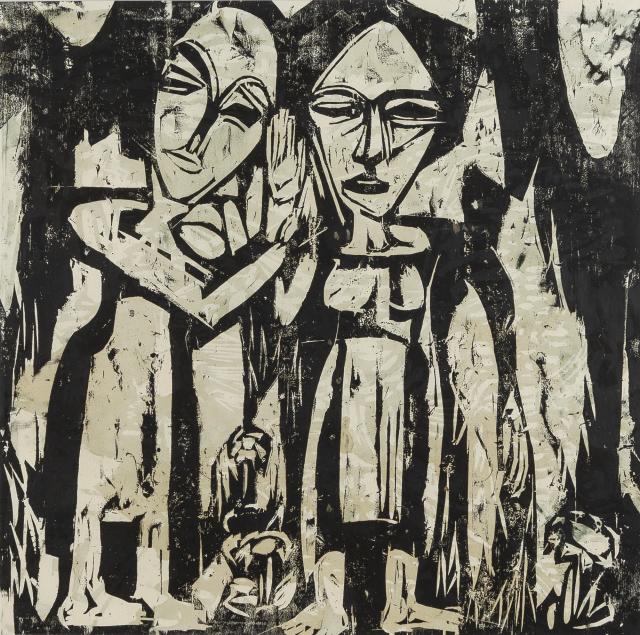

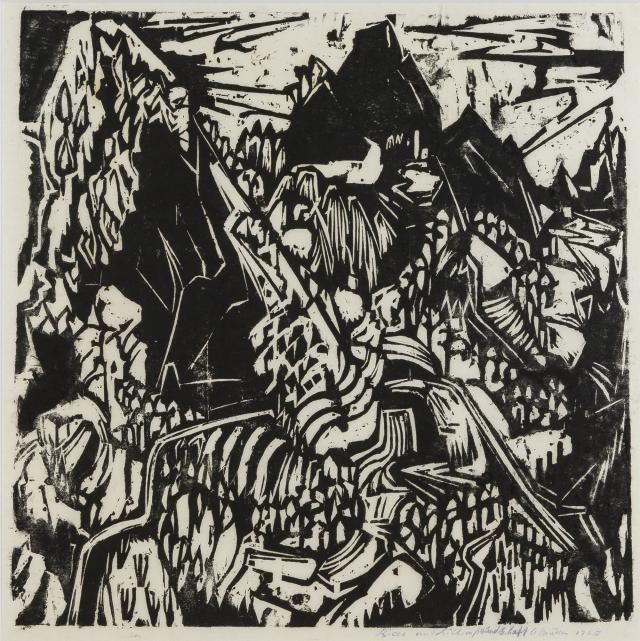

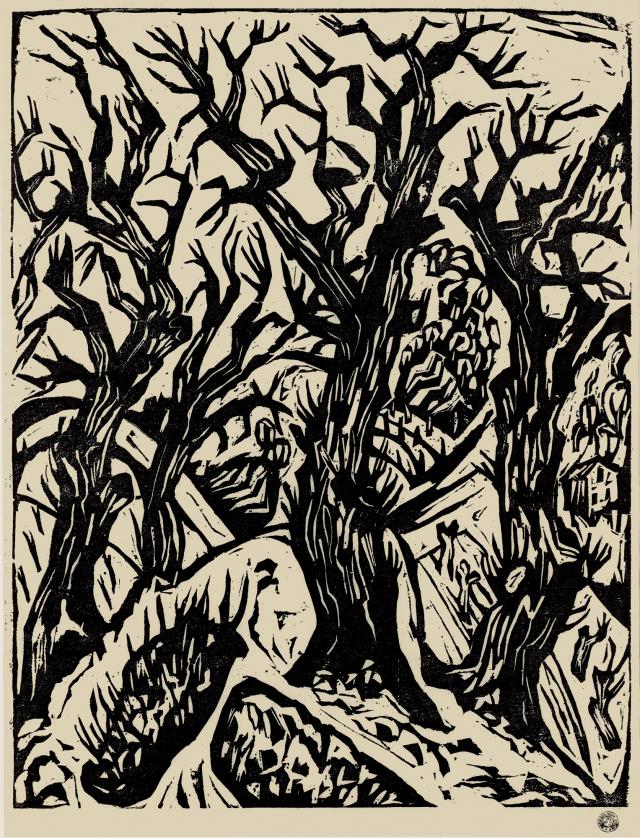

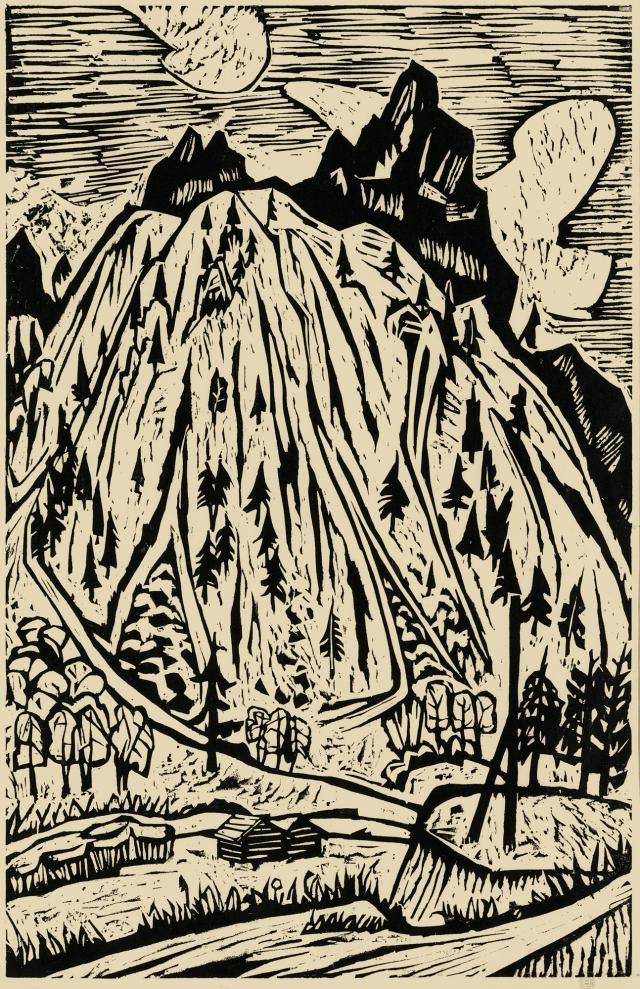

Kirchner’s arrival in Davos in 1917 also kindled interest in expressionism among the young generation of Swiss artists. Many painters came to stay at Kirchner’s home, including Albert Müller (1897-1926) and Hermann Scherer (1893-1927). They adopted expressionist trends that came from Germany, but at the same time preserved a connection to Switzerland’s pictorial tradition and folk art. Their brightly toned landscapes and superimposed planes evoke motifs of the Swiss imagination, like Müller’s Tessinerlandschaft III (1925) and Scherer’s Waldlandschaft (1924-1925).

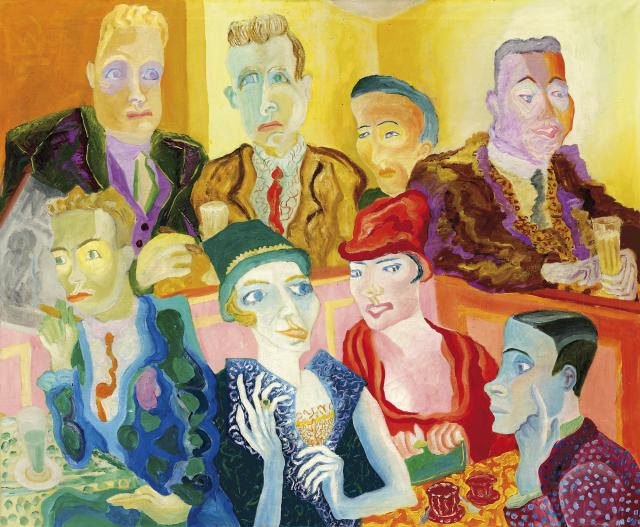

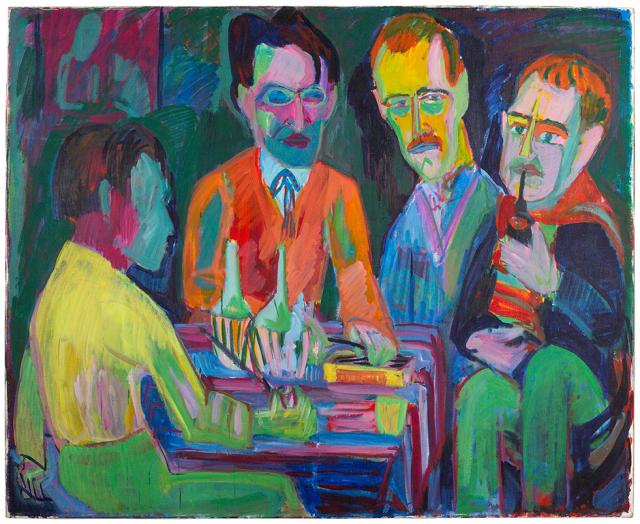

In 1925, Müller, Scherer and Paul Camenisch (1893-1970) founded the Rot-Blau group, which called for better exhibition possibilities and more public commissions for expressionist art. Somewhat on the periphery of this group experiment, Camenisch painted fantastical structures with acid colours (Platz, 1924), as well as landscapes (Der rote Rücken, 1926) and scenes of social life (Café Commerce Suisse, 1928). Thus he combined the precepts of expressionist painting with those of surrealism, and even those of New Objectivity, his paintings evoking a certain kind of social criticism. Despite being short-lived, the collaboration between Müller, Scherer and Camenisch in the context of the Rot-Blau group made a major contribution to Swiss expressionism, and helped it gain acceptance from the public.