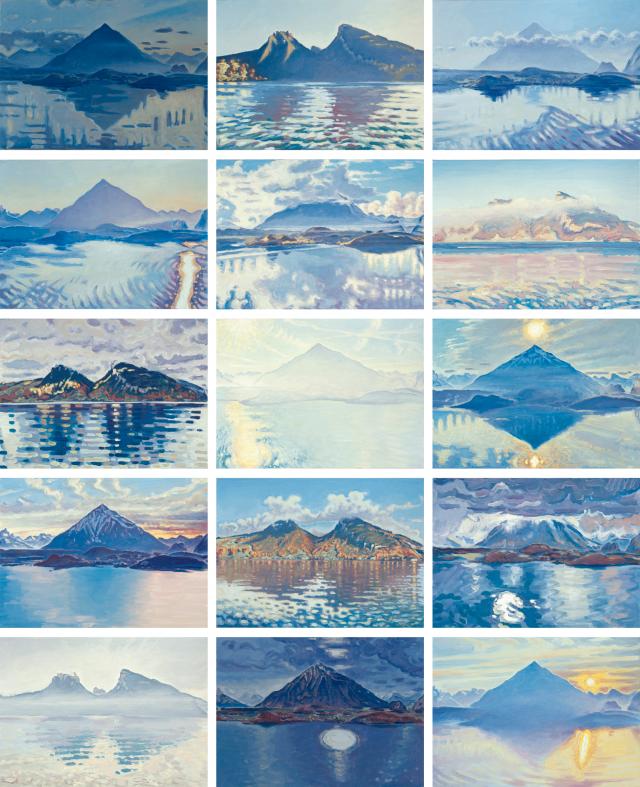

At first glance, the series Am Thunersee 1-38 (1995) by Basel artist Jean-Frédéric Schnyder brings out the archetypal image of a Switzerland of mountains and lakes. The majestic presence of the Bernese Alps and the pyramidical shape of the Niesen summit reflected in Lake Thun establish themselves as a leitmotif of the thirty-eight compositions, evoking Ferdinand Hodler’s expressive strokes, bright palette and rhythmical arrangement of forms, as well as his treatment of the alpine motif. Nevertheless, Schnyder does not content himself with an emblematic reproduction of the alpine landscape, but pastiches Hodler’s style with more casual and corrosive strokes, something that ends up triply frustrating the viewer in terms of format, authenticity and technique.

In a first phase, Schnyder’s choice of a pocket-sized format (30 x 42 cm) rules out any claim to sublime grandeur. On a noticeably reduced surface, the artist strives to give diverse expression to his implacable quest for infinite contemporary beauty. Thus Am Thunersee 1-38 appropriates the aesthetic ideal in order to drain it, through free experimentation with colour, light, gesture and composition, without really trying to rival the masters of the genre.

In a second phase, the series focuses on the idea of repetition more than on that of a singular representation of the picturesque. Reinterpreted day after day, at different times and under a variety of meteorological conditions, the image of the Swiss summits reflected in Lake Thun is gradually stripped of any claim to uniqueness and, by inference, any form of authenticity.

Finally, Schnyder’s pictorial practice proves too subtle to be characterised as mere “amateur painting”. As a scholar who controls his choices and references, Schnyder works on a veritable deconsecration of contemporary beauty. Appropriation and citation only constitute a working method, as his attention lingers over various facets of everyday life. Whether it be the construction, style, subject or format, one of these elements always leads the painting towards the present, understood in its materiality and ordinariness.

During the 2014 exhibition “Ferdinand Hodler/Jean-Frédéric Schnyder” at the Kunsthaus Zürich, Peter Fischli noted that it was Schnyder’s interest in developing a “catalogue of concepts” and a “collection of forms of expression” that made him unique. Contrary to the dominant artistic currents of the 1990s, he audaciously revived the tradition of figurative painting, arguing for recognition of the unspectacular, the insignificant and the unusual in art. Schnyder does not spurn any form of expression, any technique. Every subject that concerns day-to-day life is legitimate: waiting rooms, motorways, views of churches, public benches, or urban furniture, and even dog-waste bins. “I wanted to paint everything so no one could catch up with me”, he admitted in an interview with Josef Helfenstein. “I wanted to cover everything—every possible subject: the picturesque, the modern, all beautiful places.”

“Each day, he transforms meaninglessness into meaning [...] with the discipline of a skeptic and the passion of a lover”, in order to constantly confront viewers with their own aesthetic expectations.

In a first phase, Schnyder’s choice of a pocket-sized format (30 x 42 cm) rules out any claim to sublime grandeur. On a noticeably reduced surface, the artist strives to give diverse expression to his implacable quest for infinite contemporary beauty. Thus Am Thunersee 1-38 appropriates the aesthetic ideal in order to drain it, through free experimentation with colour, light, gesture and composition, without really trying to rival the masters of the genre.

In a second phase, the series focuses on the idea of repetition more than on that of a singular representation of the picturesque. Reinterpreted day after day, at different times and under a variety of meteorological conditions, the image of the Swiss summits reflected in Lake Thun is gradually stripped of any claim to uniqueness and, by inference, any form of authenticity.

Finally, Schnyder’s pictorial practice proves too subtle to be characterised as mere “amateur painting”. As a scholar who controls his choices and references, Schnyder works on a veritable deconsecration of contemporary beauty. Appropriation and citation only constitute a working method, as his attention lingers over various facets of everyday life. Whether it be the construction, style, subject or format, one of these elements always leads the painting towards the present, understood in its materiality and ordinariness.

During the 2014 exhibition “Ferdinand Hodler/Jean-Frédéric Schnyder” at the Kunsthaus Zürich, Peter Fischli noted that it was Schnyder’s interest in developing a “catalogue of concepts” and a “collection of forms of expression” that made him unique. Contrary to the dominant artistic currents of the 1990s, he audaciously revived the tradition of figurative painting, arguing for recognition of the unspectacular, the insignificant and the unusual in art. Schnyder does not spurn any form of expression, any technique. Every subject that concerns day-to-day life is legitimate: waiting rooms, motorways, views of churches, public benches, or urban furniture, and even dog-waste bins. “I wanted to paint everything so no one could catch up with me”, he admitted in an interview with Josef Helfenstein. “I wanted to cover everything—every possible subject: the picturesque, the modern, all beautiful places.”

“Each day, he transforms meaninglessness into meaning [...] with the discipline of a skeptic and the passion of a lover”, in order to constantly confront viewers with their own aesthetic expectations.