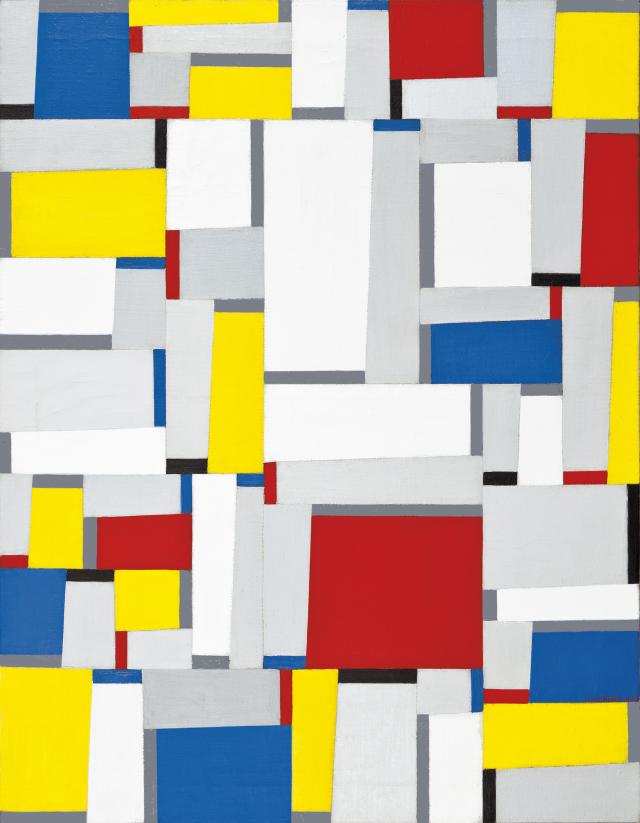

This painting, the result of progressive experimentations towards a purified language that Fritz Glarner had already undertaken in Paris during the 1920s, is characteristic of the geometric abstractions produced by the artist in New York from 1940 onwards. Strongly influenced by the Neo-Plasticism theory of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), from the Dutch artist’s oeuvre Glarner borrowed the composition’s simplified formal vocabulary as well as its architectonic structure.

Without ever renouncing his admiration for this pioneer of abstraction, but concerned with establishing his own artistic approach, he threw the rigorous orthogonal framework off balance by introducing slightly oblique lines (of 15 degrees). Almost imperceptible, they nevertheless managed to create a subtle sensation of movement accentuated by an irregular rhythm, to which his mature works would henceforth be subjected. As well as the three primary colours, and the pure black and white of Mondrian’s palette, Glarner employed several tones of grey, better suited to adding a spatial dimension to his compositions. Although very discreet, these modifications of forms and colours succeeded in giving birth to a dynamic language marked with vitality, which the artist elevated to an aesthetic philosophy baptised Relational Painting.

This ambitious title, which from then on would be given to all his paintings, not only referred to the relation that each element maintained with the others within the image, comprehended as a balanced whole, but also described the particular bond woven between these works and the spectator’s perception. It was indeed this interaction and this ongoing dialogue that Glarner wished to nurture through his numbered series of homogenous compositions which, even once they became familiar, would never cease to be a new experience for the attentive onlooker.

Without ever renouncing his admiration for this pioneer of abstraction, but concerned with establishing his own artistic approach, he threw the rigorous orthogonal framework off balance by introducing slightly oblique lines (of 15 degrees). Almost imperceptible, they nevertheless managed to create a subtle sensation of movement accentuated by an irregular rhythm, to which his mature works would henceforth be subjected. As well as the three primary colours, and the pure black and white of Mondrian’s palette, Glarner employed several tones of grey, better suited to adding a spatial dimension to his compositions. Although very discreet, these modifications of forms and colours succeeded in giving birth to a dynamic language marked with vitality, which the artist elevated to an aesthetic philosophy baptised Relational Painting.

This ambitious title, which from then on would be given to all his paintings, not only referred to the relation that each element maintained with the others within the image, comprehended as a balanced whole, but also described the particular bond woven between these works and the spectator’s perception. It was indeed this interaction and this ongoing dialogue that Glarner wished to nurture through his numbered series of homogenous compositions which, even once they became familiar, would never cease to be a new experience for the attentive onlooker.