The history of Art Brut is closely tied to that of French artist Jean Dubuffet, who made his first prospecting trip into Switzerland’s public mental health institutions in 1945. As he established contacts with doctors, but also with writers and artists, Dubuffet became aware of a different kind of creative practice that seemed to elude all academicism: that of misfits, outcasts and rebels, kept at arm’s length from society. The works created by these autodidacts “unscathed by artistic culture” (Jean Dubuffet, 1949) display extreme spontaneity and freedom, a certain sense of wildness that fed on the deepest, purest human impulses.

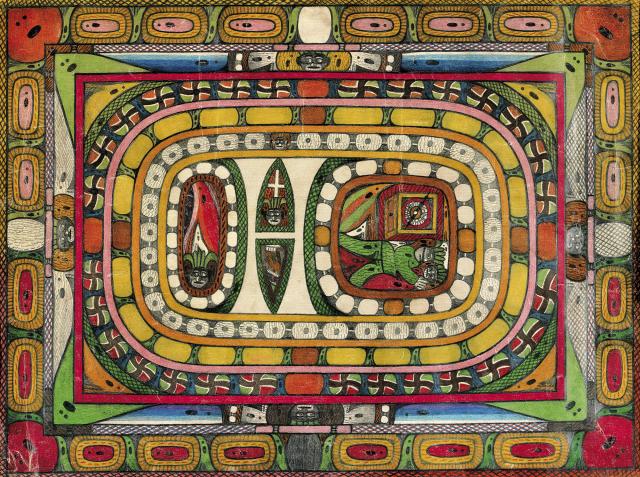

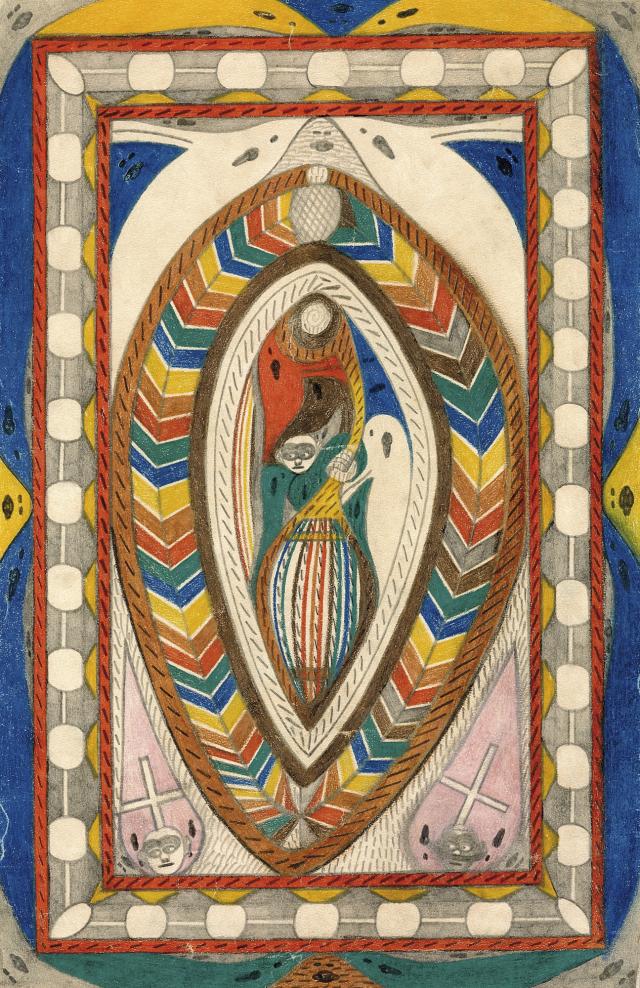

Unlike naive art, which we also owe to autodidacts, Art Brut had no aspiration to institutional recognition, and therefore did not seek to reiterate recognised subjects and genres. The works of Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930) testify to his lack of any academic mimesis or any desire to become part of the official history of art. Despite the fact that André Breton considered him one of the three most important artists of the 20th century, Wölfli did not produce his works for other people’s eyes. They remained private, impulsive, unpredictable explorations, articulated according to their own logic, revealing unusual creative processes and means.

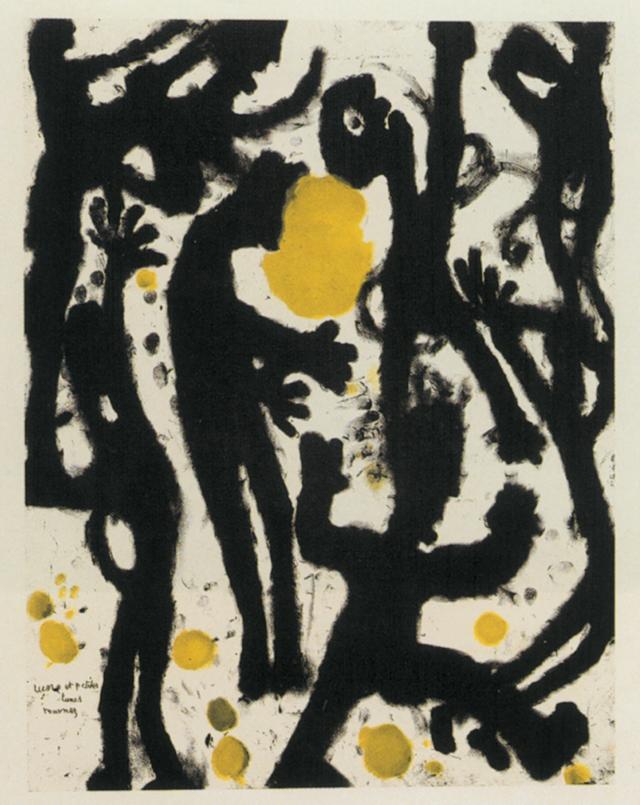

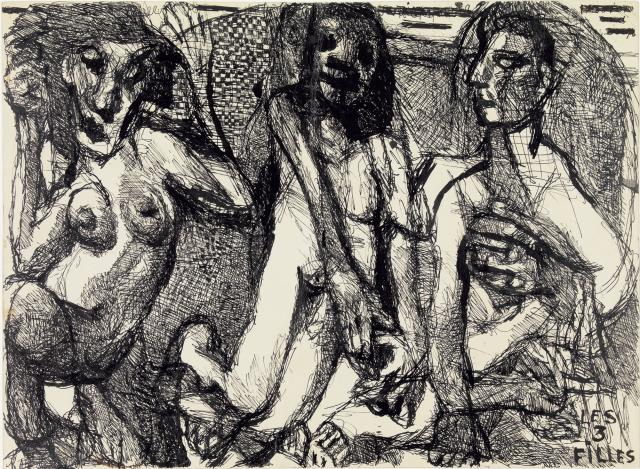

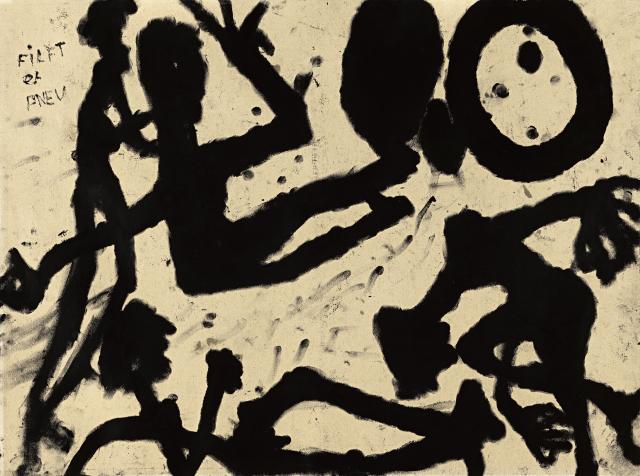

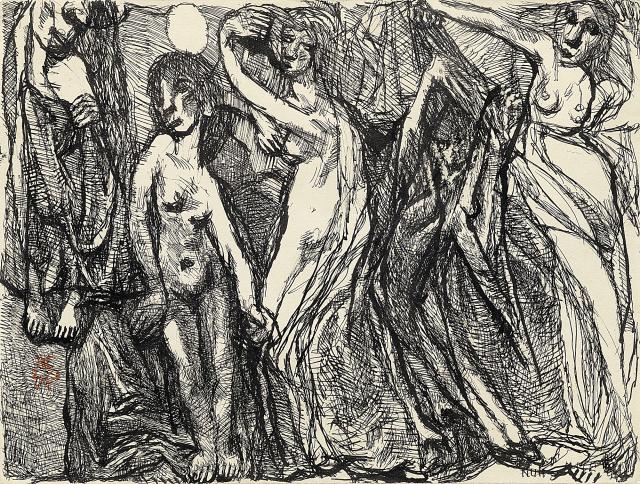

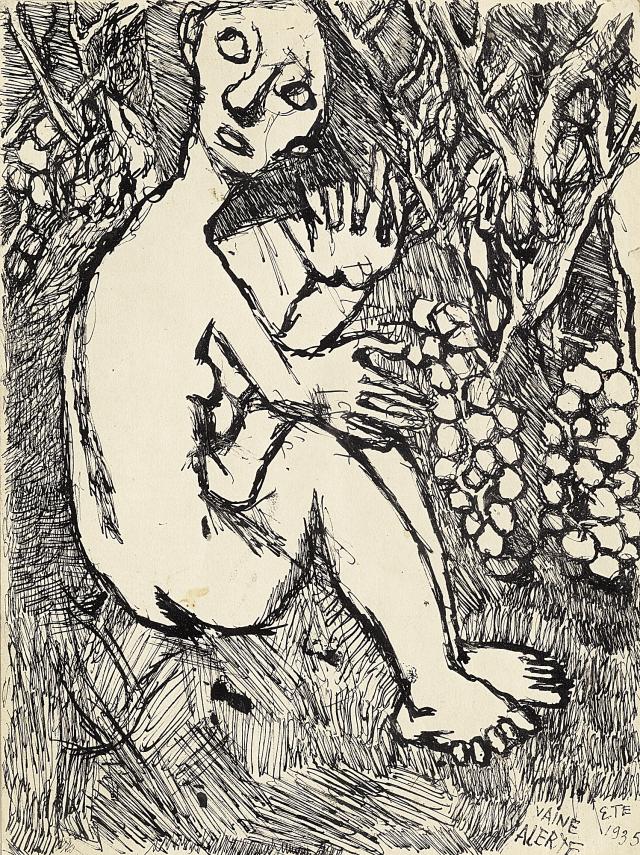

This is something that his work had in common with that of artist Louis Soutter (1871-1942). During his nineteen years of forced retirement in an asylum in Ballaigues, Soutter created over two thousand eight hundred paintings and drawings of a unique kind. However, unlike the artists of Art Brut, Soutter had received an education in art, and was fully aware of the art of the past and present. Today, his work is still associated with Art Brut, even if it anticipated the tachisme and informal art of the post-war period.